Ghosts in the Balcony: A Cross-Country Trip to 58 Theaters Fighting to SurviveIn the worst October for moviegoing since the ’90s, I crossed 20 states to hear the primal screen from people keeping film alive — even when Hollywood won’tAs the cliché goes, write what you know. At The Ankler, I’ve focused on my generation — Gen Z — whether it’s about the power of clip channels, Hollywood’s IRL experiences boom, or the AI wars at film schools. Starting today, I’m writing Crowd Pleaser — a new Letterboxd × Ankler project about the only greenlight that matters: the audience. For my debut column, I proposed a cross-country drive to America’s movie theaters. Far from the shiny temples of L.A.’s TCL Chinese Theatre or AMC Lincoln Square in New York (the final stop on my tour), I drove my rental Subaru Outback 4,050 miles to uncover the moviegoing struggles in what Hollywood often refers to as “the middle.” I met theater owners so starved for product they’re showing reruns of Monster House and Monty Python, and an owner who had to shut down his theater for the night after ZERO people came to watch A24’s The Smashing Machine. My journey took on greater urgency the more I drove as the box office — devoid of new movies — marked its worst month since the 1990s. But movies matter. There are huge, hungry fans everywhere I visited, all of whom want MORE out of Hollywood: families who need a place to entertain the kids, slight-to-extreme cinephiles desperate to be entertained, retirees wistful for quality films. How desperate are they? Fans are coming to theaters even without new movies just to buy the popcorn to take home. My reporting is a plea to Hollywood to recognize the opportunity of an audience begging for more. Follow my trip on Ankler’s Instagram (@theankler) and more exclusive details from the road on Ankler’s YouTube channel. And email me about going to the movies: matthew@theankler.com. Now here is my story. It’s a cool October Friday night in Pagosa Springs, Colo., a working-class town of roughly 1,800 that’s proudly home to the world’s deepest hot springs. I’m nearing the end of day three of my two-week cross-country voyage, and with an hour to kill, I post up at a small bar, where several locals drink beers while watching a playoff baseball game on the corner TV. The town itself is a beauty, with tall Aspen trees overlooking the San Juan River on one side of the road and an old Western village — now transformed into a slightly more modern town, featuring Subway and Arby’s next to century-old local shops — on the other. There’s the Pagosa Hotel, which burned down, then was rebuilt in 1919; there’s Goodman’s, a fifth-generation family-owned department store that’s been in operation since 1899; and right next to it is the Liberty Theatre, a charming, old-school auditorium that has remained in business since 1919 and once housed a brothel in what are now the dark, gravelly bowels of the venue. I’m in town as part of my quest to spend quality time at as many American movie theaters as I can, traveling by car from Los Angeles to New York to 20 states and 58 movie theaters. Guiding me through stop number 16 is Liberty manager Ann Sanders, a New Orleans native and soon-to-be great-grandmother who sports bright red hair and medium-sized glasses. Two weeks after Hurricane Katrina struck, Ann sold her multi-million dollar wholesale and marketing company to a competitor. She subsequently moved West and eventually settled in Pagosa Springs, which she refers to as her “happy place.” In 2018, her best friend of nearly 50 years purchased the Liberty and entrusted Ann with managerial duties, which she spends her time on, including programming, advertising and overseeing the day-to-day operations of the 200-seat venue. As a few customers begin to file in, Ann rushes to tend bar — a relatively new addition to the space. After Ann’s friend bought the theater, she began renovations, which took two years to complete. (There is no exact estimate on how much the renovations cost, but Ann points me to a hand-painted mural of the block behind the concession stand. Instead of “Liberty Theatre,” it reads “Money Pit.”) According to Liberty employees Teresa and Al, these renovations were sorely needed. As a memento, the bar area holds three of the old stiff wooden chairs, one of which has a small hole in the center, which is believed to be from a gunshot back in the 1920s. The theater is now in quite an admirable condition. It still retains much of its old-school charm, with a sign reading “Movie Tickets 25¢” and a few framed black-and-white images of the theater lining the walls. However, the seats now have a little more plush to them. The floor used to be flat, such that you’d often be staring at the back of someone’s head — now it’s sloped. The ceiling is twice as high, no longer falling in, and has a sleek tin appearance. The one thing that couldn’t be renovated out of the venue, though, were the ghosts. According to Ann’s psychic friend, they remain from the Prohibition-era bordello in the basement. While touring me through the premises, she briefly alludes to it: “We do have ghosts, by the way.” I laughed it off as a joke. But while talking with Teresa and Al as Ann tended bar, they brought it up just the same as she had: matter-of-factly, shrugging it off as a quirk of the building. I ask Teresa, who sometimes feels a little tinge on her skin when she goes downstairs, if she’s afraid of them. She shakes her head no. “They’re not evil spirits,” Teresa says. “They’re just quietly living their life like they normally do.” That Friday night, there are likely more ghosts occupying the premises than moviegoers. As Ann and I sit in her dimly lit projection room, we overlook the eight people who have made it out for a showing of the Jennifer Lopez musical flop, Kiss of the Spider Woman. Meanwhile, Ann regales me with stories of small-town theater management. Many are funny. When A Minecraft Movie opened at the Liberty, she hung signs all around town that read, “Disruptive Behavior Will Be Prosecuted.” “Will be prosecuted?” I ask. “Absolutely,” Ann replies. “We’re friends with the sheriff.” Some stories are sad. The first week of last year’s Joker: Folie À Deux was so bad (only three people came one night), she had to lay off her staff and work everything herself. But a lot of what she says is the type of wistful, cynical rhetoric I would begin to hear across the country, at every independent theater, multiplex and chain; urban, suburban and rural; managers, employees and patrons alike. “Streaming is making people want to sit at home,” Ann says. “Economics affect that. Right now, I think people are afraid of everything going on in the world and our country, and I think they’re holding on to their money. And that’s why I keep doing all these, instead of just movies, events.” Ann is referring to her diverse slate of alternative programming, which ranges from a “Cocktails & Comedy” show once a month, to concerts, general venue rentals and what she calls her “pop culture movies.” She sold out a screening of 1975’s Monty Python and the Holy Grail, replete with goodie bags and coconut cups. She had her best night with the 1982 musical fantasy Pink Floyd — The Wall, and did well on a screening of 1994’s Pulp Fiction, where she gave out little bags with mock props from the film, including water guns, enamel pins, plastic syringes and small stopwatch keychains. “I mean, I’m doing everything I can to make money — everything I can think of,” Ann says. She, like countless theater owners, is getting creative at a time when new Hollywood films just aren’t moving the needle. I’m on the road, venturing into movie theaters during October, when domestic box office revenue totaled $425 million. That’s the worst October the industry has had since 1997 (excluding Covid), which is hard to wrap your head around, considering that’s not even counting for inflation. Since 2019, U.S. movie ticket sales have been down a whopping 40 percent. You can blame the quality of the movies being released, the theaters for not providing an experience worthy of leaving the couch, or a mix of both and factor in the country’s current economic situation. But regardless, in theaters across the country, many moviegoers who once came week in and week out are no longer there. Just their ghosts. I ask Ann if she feels confident that the theater will last into the coming years and beyond. She grows resolute. “As far as I’m concerned, I am going to make it last.” A Struggle with ExclusivityOn day one of my trip, I spent much of my afternoon at Barstow Station Cinema Is D’Place, a six-screen theater about halfway between L.A. and Vegas that’s managed by the kind and talkative Michael, a goateed father of five who sports what looks like a gray mechanic’s uniform, paired with a bright orange Tennessee Vols hat and, naturally, a thick Tennessee accent to boot. During October 2020, when the pandemic was in full swing, the theater averaged 15-20 people per day, regardless of the movies being shown. Now, the average weekend day is about 50 to 60, with decent movies pulling in more like 100-105. The occasional great film — like Lilo & Stitch or The Super Mario Bros. Movie — notches 300 people. To break even on a given day, Michael says the theater needs just 50 moviegoers on a weekday and, with more labor required, 75 on a weekend. So, Barstow Station is doing alright; it’s still generating enough revenue to justify its continued operation. But Michael has one big complaint about why it’s still not what it should be. “Beforehand, it was supposed to be a contract for 45 days or more. But when you release a movie the same day to the theater, you can literally buy one on Prime that night,” he says. “I mean, spend $100 at the theater or spend $20 at home: what are you going to do?” For most consumers, it’s not a tricky question to answer. Tom and Kris, an early-60s couple at an AMC in Birmingham, Ala., “don’t go to movies hardly at all,” Tom says. They would come often when their kids were still young, but now, it’s a three-times-a-year occurrence. Why? “You can wait a month and watch it at home,” Kris says. During Covid, then-WarnerMedia CEO Jason Kilar infamously debuted “Project Popcorn,” an initiative that brought his studio’s films to HBO Max at the same time they were released in theaters. What was supposed to be a temporary measure became a habit for Hollywood. Not long ago, films had a 74-day window during which they could not be rented or purchased at home after their theatrical release. Now, studios regularly put their movies on PVOD 45, 30 — even 17 days after their initial outing. So instead of 74 days, theater owners are left fighting for two weeks. Anything to remove the all-too-real feeling that you really don’t have to make it to a theater for any given release. On day two, I make it out to Kingman, Ariz., a city with a population of 30,000 that has just one movie theater: Brenden Theatres Kingman 4. The story is the same. “There aren’t too many good movies that people want to see as much, especially when most of them in the first place are already being bought on streaming services,” Will, the theater manager, says. “Whatever we do get, people could just wait a month, or even a few weeks, and just watch it at home.” It all traces back to Covid, which, even aside from the window shrink, was the focal point of the industry’s decline. It’s hard to overemphasize just how much of a nuclear bomb Covid was to these theaters. Not only was it a year (and in some cases, more) of virtually no business, but it also caused consumers to lose the habit of actually going to the theater. Throughout my time on the road, it was the topic that came up most frequently with owners and managers, who would often bring it up unprompted. Each has their own story of making ends meet somehow, someway, or what the theater used to be like before Covid, compared to now. Currently, Brenden Theatres Kingman welcomes roughly 70 people per day. But Veronica, another manager, remembers when there were lines around the block for Marvel or big animated releases, which drew in upwards of 1,000 on their best outings. Considering that many people now have solid streaming setups at home, prices have concurrently increased, and piracy remains a significant issue. It’s all a perfect Molotov cocktail hurled at American movie theater screens, even as interest in movies themselves remains high, with strong online communities flourishing on Letterboxd and Reddit — not to mention in real life at repertory screenings like Liberty Theatre’s Monty Python event. Discount TuesdaysThe first set of people I talk to in the South, on a balmy Tuesday morning in Tupelo, Miss., are Dianne and Claire, who come every discount day to their local Cinemark in Tupelo. Dianne is a kind Southern woman who appears to be in her mid-60s, and her daughter, Claire, is a woman in her 30s with Down syndrome. They come for what Dianne terms the “children’s shows,” and in particular, they enjoy Pixar films and any other kind of animated fare. “It’s got to be PG,” Dianne tells me. So, what is this older woman and her daughter going to see there this afternoon? Tron: Ares, the PG-13 sci-fi action movie starring Jared Leto. “I want there to be more family shows because the only thing we could find… this is the only PG-13 show,” she says, noting that they’ve already seen the only other kids’ film available, Gabby’s Dollhouse. Gabby’s Dollhouse is technically rated G, as it’s a movie for an especially young cohort, so if we exclude that film, there have been precisely zero PG studio releases since Freakier Friday on Aug. 8, with the next one being Wicked: For Good on Nov. 21. That’s three and a half months without a down-the-middle family film, which is a level of negligence on the part of the studios that makes your head spin. (In 2019, there were six studio releases with a PG rating between the Freaker Friday and Wicked window.) In addition to the uniform consensus that Discount Tuesdays, when tickets are typically 50 percent off, are the hottest time of the week, every employee at virtually every type of theater will answer the question of “Who mainly comes here?” with the same answer: old people and families. The necessary caveat is that when school’s out in the summertime, it is the period that studios tend to release their films. But as every company that releases movies contributes to a 10-car summer pileup, there’s a wide-open road during the fall that goes totally unexploited, leaving consumers like Dianne and Claire stuck watching cyberpunk sci-fi. All areas of theatrical production are down, owing to Covid, the strikes and general contraction, but kids’ movies have somehow become chief among them. At UEC Theatres in Cambridge, Ohio, a woman named Misty sits with her husband and their 8- and 12-year-old daughters, waiting for the movie Good Fortune to start. The Aziz Ansari-directed comedy is not like watching Eddie Murphy Raw, but it is still an R-rated movie. Misty is pretty calm about it, but when I ask her if this would’ve been her preferred movie to watch with her kids, she says she “was kind of annoyed” upon seeing the available options. For every Dianne and Misty, there are plenty more parents who saw what was playing and opted to do a movie night at home, where something like KPop Demon Hunters has spent months in Netflix’s top 10 and generated so many millions of views that the streaming service successfully reversed windowed it into theaters twice. On day 10 of my trip, I’m sitting through the trailers of Sony’s Crunchyroll anime hit Demon Slayer… at a showing in a Charleston, W. Va. theater, when I meet Nick and Ivory, a young married couple with a young, energetic son. With the afternoon off, they’ve made it out to the theater — something they only do two or three times a year. Back when he was growing up in Boone County, Nick would come twice a week with his aunts, and he misses the feeling of a packed theater. Now Nick and Ivory’s son “loves it,” he says, and when the family comes, they try to book a row without any other people in it because of how he runs around during films. So, Nick just bought a subscription that gets them $10 off each month in the hopes of going to the theater more. The thing that’s holding them back, like many families, is the absurd cost of a trip to the multiplex. “Popcorn and two drinks cost us almost $30. It really adds up fast,” he says. “And tickets, I don’t know how to keep up with the prices on them because today I bought them for $12.50 apiece, and other times I come, they’re $24.” In keeping with the rest of the economy, movie ticket prices have risen in line with inflation. The average ticket price in Q4 of last year reached $11.64. For many theaters, price hikes were necessary after vendors began charging more for food and beverage supplies, and there were insufficient customers to offset the additional expenses. However, unlike eggs or rent, filmgoing is not considered an essential commodity (at least not by definition). As a result, fewer people show up, prices continue to rise to account for the decline, and we’re left with the current mess. Project PopcornEven if people aren’t going to the movies as much anymore, they’re still looking for the experience (and the snacks). As ever, it’s not ticket sales that bring in bucks for theaters, but concessions. Within the industry, this is a well-known fact, and the numbers speak for themselves. In the three months between April and June of this year, AMC Theatres generated 55 percent of its revenue from admissions and 45 percent from food, beverages, and other commodities, including merchandise. In the same period, Cinemark generated just under half of its revenue from ticket sales, with the remainder coming from concessions and other sources. At independent and small chain theaters, this is much the same. None of this is new, but what is new is how that concession money is coming in — and out — the door. At the two-screen Fiesta Theatre in Cortez, Colo., popcorn sales have remained the same from pre- and post-Covid. But now, “We offer popcorn just without watching the movie, our big ’ol to-go bag, and that’s actually become super popular after Covid,” manager Jordan tells me. The theater averages 25-40 people a night this time of year. On the Friday before I got there, she said they sold 15 big ’ol to-go bags, which was the most they’d sold in a day.

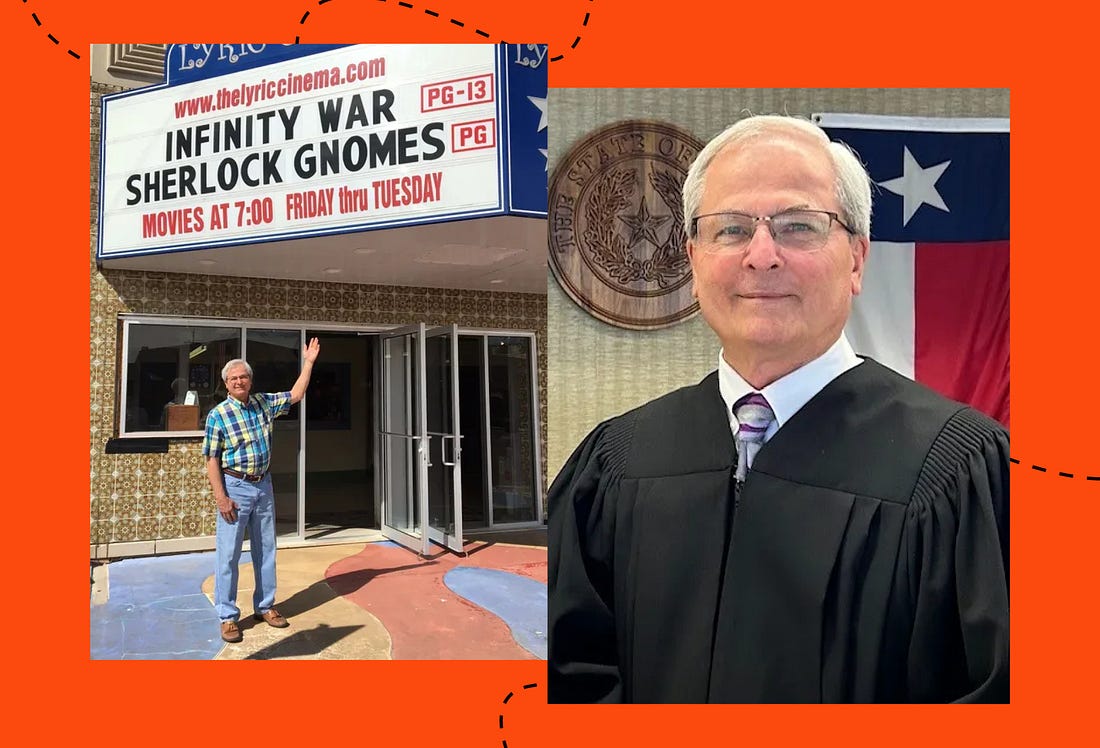

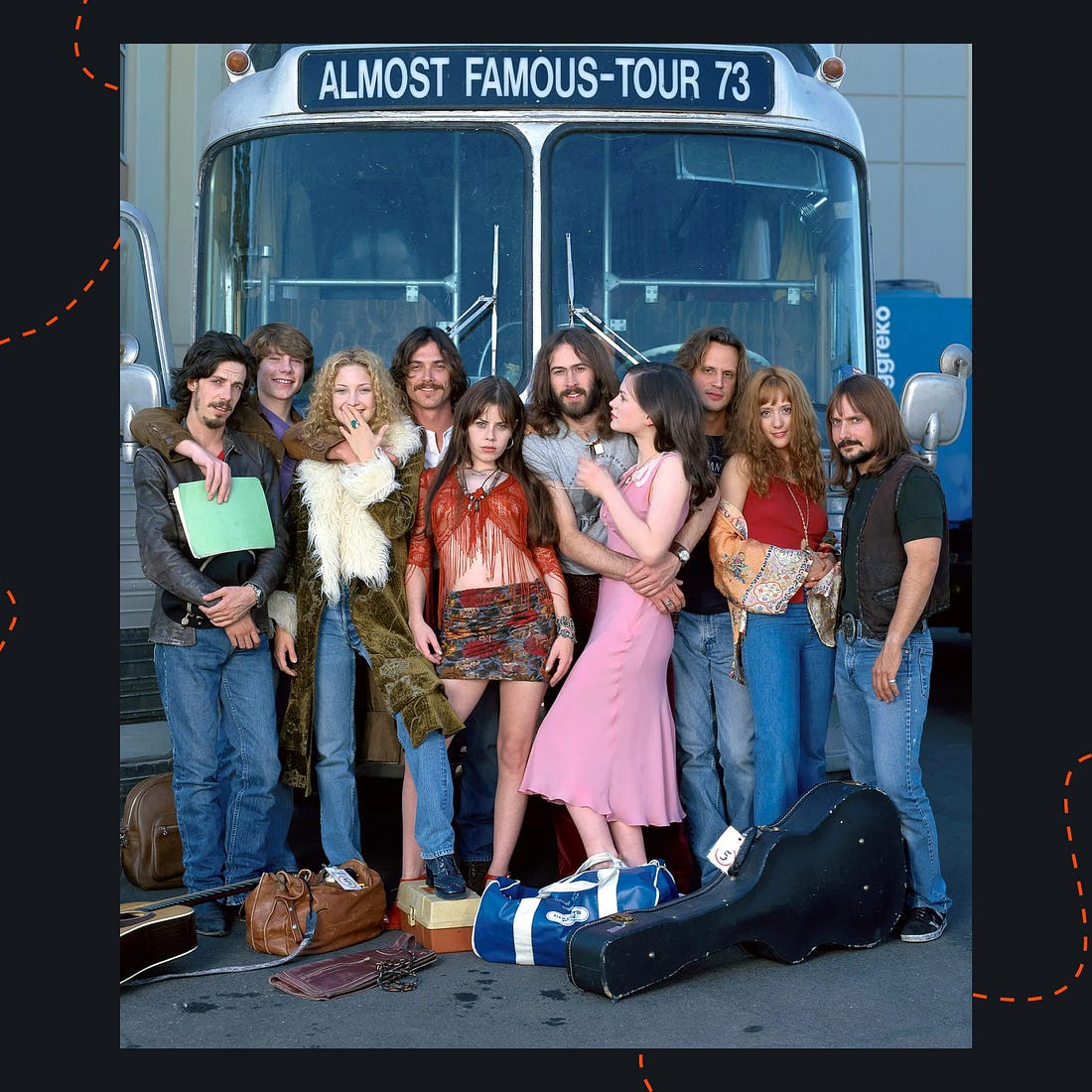

When I ask her if she gets the impression that people are buying popcorn to watch movies at home, she notes that’s probably the case. “Just because life has gotten expensive, and we’ve had to raise prices, mainly with our concessions,” Jordan says, “to accommodate everything else going up.” Since she started, they’ve raised prices $3-$4, with tickets now costing $9.50-$12. It all factors into a calculus for consumers where it makes more sense to pay for some authentic movie theater popcorn, but not the movie theater itself. Fiesta Theatre is just one of many venues employing this new to-go popcorn tactic. At Legacy Theatres in Bristol, Va. (where the chicken tenders and fries were the best concessions food I had on the entire trip), they sell “Party Popcorn” bags, which have “Available for Take Out Only” written directly on them. The next evolution for theaters: DoorDash. AMC Theatres has been using the delivery service for a couple of months, while Cinemark began participating last year. If you look at the DoorDash app, you can find both movie chains offering pickup or delivery — no moviegoing required — on popcorn bags, Icees, flatbread pizzas and more. And at the actual locations themselves, right next to the concession stand, are signs that read, “DoorDash Pick Up Here.” In a case of divine journalistic timing at one Pennsylvania AMC I visited, the three employees behind the concessions stand started scrambling upon receiving their first-ever giant DoorDash order. “Do we bag it?” one of the crew members wondered aloud. A woman named Brittany had placed a delivery order for two chicken tenders, two drinks, two pretzel bites and a couple more items. At a northeast Cinemark, I asked one of the employees how often people order their delivery. “Every day. You’d be surprised,” he tells me. “Most of the time, they get popcorn. Sometimes they get nachos. Sometimes they get a hot dog.” Keeping Up the FightSince it opened, Lyric Cinema in Spearman, Texas, has been owned by two families: the Hales and the Ellsworths. In 1976, Alton and Peggy Ellsworth purchased the theater from the Hales and went on to operate it for another 24 years. Helping them with the day-to-day tasks was their son, Gary Ellsworth, who spent many nights sleeping in the big red chair of the theater’s office while his dad handled the books. Come 2000, Alton had health issues and decided it was time for him to step away. “Well, I’m gonna close the theater,” Gary recalls his dad saying, “unless you want to become the owner.” Gary resisted until one day his two daughters offered to help him run it and asked him, “Don’t you remember how much fun you had growing up around here?” That was enough for Gary, who, on March 16, 2001, fired the theater back up with a showing of Cast Away and a romantic drama starring Julia Stiles. Twenty-four and a half years later, I’ve made my way to the Lyric in the hopes of meeting Gary. I’m lucky to have come on a Saturday night. On Fridays during football season, he provides play-by-play commentary for the Spearman High School team’s games, leaving theater operations to his daughter Jana and her husband. In addition to the theater, Gary, 76, is also a city judge, handling Class C misdemeanors, traffic violations and other minor offenses. That Saturday night, we talked in front of the upstairs screen, which went vacant as Tron: Ares played to seven locals downstairs. Gary indulges me as I ask my litany of questions about the state of his theater. He tells me not a single person showed up for The Smashing Machine, A24’s failed mixed-martial arts drama with Dwayne Johnson, the week before, and why, after Covid hit, he just knew things wouldn’t be the same again. But mostly, Gary wants to talk about the history of the Lyric. Every nook and cranny of this place has a story from the nearly 50 years his family has owned it. The most evocative: Up in the balcony, an unstable man once strapped an M80 firecracker to a pigeon he’d brought in. When the man set the pigeon loose, it thought the screen light was outdoors and flew straight into it, causing the pigeon to explode in the middle of the audience. Gary grins from ear to ear, walking me around, letting me in on the history of each artifact. For instance, the Lyric popcorn machine has been there since Gary was a junior in high school and was the first one off the assembly line in 1966, as evidenced by its serial number (no. 66001). But 25 years after his father relinquished the venue, Gary is doing the same at the end of the year. He and his wife want to travel more, and after their third great-grandchild is born, it’s time to take a step back. As he explains his rationale, he slows for a beat and looks up. “I don’t know what dad and mom are doing up there in heaven or wherever, saying, ‘Maybe it’s about time,’ or, ‘Maybe you ought to stick it out a little longer.’ I don’t know.” For the rest of the film industry — including theater owners and audiences of all ages — the decision is not whether to step away, but how to move forward. Whether to evolve and grow in areas like theater quality, investment, film output and new revenue streams, or whether to fold in on itself and allow dirty auditoriums, collapsing theatrical windows and IP fodder to continue the industry’s descent. “But it’s getting over that hump of making that darn decision,” Gary says. “It just drives you nuts.” So Hollywood: don’t read this as an obituary. Read it as a to-do list. The crowd is waiting; the doors are open. Now give them something worth leaving the couch for — and price it so they can come back next week. Happy trails. Now From Letterboxd: On the Road AgainLetterboxd members reveal their favorite road trip moviesWhen Letterboxd members voted on their favorite road movies in a Showdown a few years ago, they didn’t take only one route. They saw the road movies that cast America in a new light, the way a cross-country journey can be personally transformative, or just admired the need for speed. Easy Rider, Dennis Hopper’s seminal 1969 movie, takes viewers across a changing America. Still, as Letterboxd member Nea observes, the movie has you, “Setting out to see the nation you belong to.” Preet responded to the emotional honesty of Alfonso Cuarón’s 2001 favorite Y Tu Mamá También, noting, “What’s more teenage than being horny, angry, and emotionally wrecked?” Sometimes it’s just the little, unexpected moments that stay with viewers, just as they’ll stay with the character. “I’m never gonna be able to hear ‘Tiny Dancer’ without thinking about the scene on the bus ever again,” writes Betty about Cameron Crowe’s 2000 classic, Almost Famous, “and I’m perfectly content with that.” Or failing that, what viewers really need, to quote Eleanor Roosevelt (by way of 2006’s Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby), is “hot, nasty, badass speed.” That’s when you pop on one gigantic chase with George Miller’s Oscar-winning 2015 hit, Mad Max: Fury Road. “This is a great film to watch right before your driving test,” declares Alor (although it isn’t recommended to shout, “Witness me!” at your local DMV employee). The road never ends, and audiences have loved riding along with this year’s One Battle After Another, an Oscar frontrunner for Paul Thomas Anderson and Letterboxd’s highest-rated movie of 2025 at the time of writing. “Watching that car chase on the third-largest screen in the world made my stomach turn like I was on a fucking roller coaster,” says Ash about the film’s unforgettable climax. Or, as A sums it up, One Battle is “an absolute insane and wild ride from start to finish.” — Matt Goldberg for Letterboxd Got a tip or story pitch? Email tips@theankler.com ICYMI from The AnklerThe Wakeup Universal enlists Sabrina, Netflix re-enlists Luther Film Crowdfunding 2.0: An Indie Studio Got 60,000 Fans to Invest $25 Million. How? Ashley Cullins reports on how players like Legion M, Bleecker Street and Eli Roth’s Horror Section are turning to ‘fan-vestors’ to finance films and activate audiences The Death of Dramatic Films: Hollywood Fades into Emotional Flatline Richard Rushfield asks: Are we really okay with just white men making action comedies? The Art of Hooking Audiences: Execs From a Disney-Backed Microdrama App Tell All DramaBox’s creative team came from traditional Hollywood. Now aiming for $3B in revenue, they tell Elaine Low how they’ve had to unlearn almost everything 100 Days at Paradance: Warners, Trump & the Ellison Checkbook Plus: Richard opens the reader mailbag on the dearth of women directors The Women at the Heart of Making Sinners How artisans Ruth E. Carter, Hannah Beachler and Autumn Durald Arkapaw helped turn Ryan Coogler’s blockbuster into an Oscar fave Adam Sandler’s AARP Era is Here Plus: Denver Film Festival, IMAX wows & yet another Golden Globes TV show 🎬 Richard & Sean: Predator Kills It as Starry Indies Flop A bad weekend for Sydney Sweeney & Jennifer Lawrence, but Colleen Hoover’s Regretting You shows legs 🎧 Bari Weiss, MS Now & the Sad Battle for TV News’ Last Viewer (Age: 70) As Gen Z gravitates to online newsfluencers, New York legacy media is being roiled 🎧 Gus Van Sant: ‘You Have To Be Obsessed’ The Oscar-nominated director of Good Will Hunting and Milk is back with Dead Man’s Wire, his first film in almost a decade More from Ankler MediaNew from Natalie Jarvey’s creator economy newsletter: Exclusive: What 188 Influencer Marketing Deals Signal About 2026’s Coming M&A Wave ‘IMDb for Creators’: How Famous Birthdays Took Over Gen Z — and Became Agents’ Scouting Tool Andy Lewis’ latest IP picks: A Descent into LA’s Dark Underbelly & A Southern Gothic Mystery |