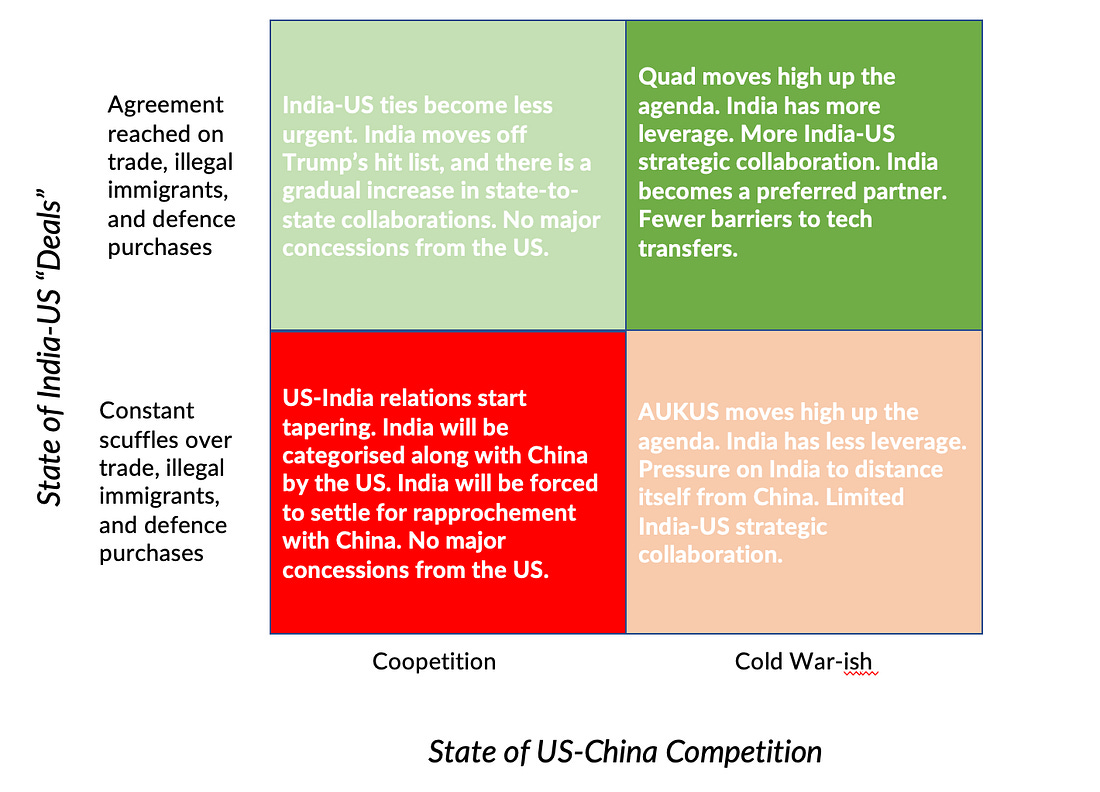

#311 Shock TherapyFrom Trump2.0 and India to Trump2.0 vs India, Examining the Q1 Results, and Intriguing Features of Kolkata's Urban Transport PoliciesCourse Announcement: If you're reading this newsletter, it's fair to say you're already in the business of anticipating the unintended. If you'd like to sharpen that instinct with formal training in policy thinking and analysis, the 12-week Graduate Certificate in Public Policy (Advanced Public Policy specialisation) is perfect. As a first, readers of Anticipating the Unintended are eligible for a 10 per cent fee waiver. In the application form question, "How did you hear about the GCPP?", select "Other" and type: I want to learn to anticipate the unintended.Matsyanyaaya: Trump2.0 and India - the Avengers editionBig fish eating small fish = Foreign Policy in action—Pranay KotasthaneThe last time we discussed Trump 2.0 and India was in February, just ahead of the Indian PM’s visit to Washington. At that time, the Indian government, anticipating Trump’s tariffs, floated the idea of a mini trade deal. The other concern back then was the deportation of illegal Indian migrants. Given these uncertainties, I proposed this framework in edition #288 to evaluate the state of India-US relations. In this framework, the two most uncertain yet important factors constituting the two axes are:

I had written that:

That trip turned out rather well. The hot potato issues of trade and illegal immigration, which could have derailed the agenda, were contained rather well, and there was a lot of continuity in technology and defence collaboration. The announcement to negotiate a mini trade deal had kicked the can down the road. Back then, I had placed the relationship in Quadrant 1. Since then, several things have changed. Musk and Trump fell out. Trump doubled down on his tariff fixation, and the April tariff rate card came in. Meanwhile, Trump backed off from economic confrontation with China once the latter brought out its repertoire of economic coercion tools. Then Pahalgam and Operation Sindoor happened. The Pakistanis were quick to hail Trump’s role in bringing the confrontation to a quick end, while the Indian side continued to assert that the US role was only a sideshow. Trump’s friendship with Putin ended, and suddenly Russia became America’s top target again. All through this, the Indian negotiators were confident that a trade deal would be struck. Then came Trump’s July 30 announcement of 25 per cent tariffs on Indian imports. He then threw in a number of rants into the mix—India buys Russian oil, India is part of BRICS, and it is a dead economy, etc. So where do we go from here? Using the same framework, I think we are now in Quadrant 3, the worst possible scenario for the India-US relationship. Following last week's events, there have been two kinds of assessments. On one side, the argument is that India should’ve done more to win over Trump by messaging his ego. Shekhar Gupta’s latest column follows this line of argument when he says:

The other side is the argument that India shouldn’t bow down to Trump’s unreasonable demands because there is no guarantee that a settlement now will not turn sour later. Former foreign secretary Shyam Saran’s column takes this view:

There are some problems with both lines of argument. The idea that India should resist Trump’s bullying seems to be a “sour grapes” situation now that the deal has disappeared. On the other hand, massaging Trump’s ego is no guarantee of assured low tariffs because it’s the one hammer he is likely to use again to achieve all sorts of goals, from ending the Russia-Ukraine war to arresting the decline of the US dollar. At the same time, both arguments drive home some truths. The first argument says India didn’t read Trump well and was outplayed by China and Pakistan in this round. The opposing argument cautions that bending over backwards to satisfy Trump’s ego carries reputational costs that will hold India in a weaker position in the next round. At this stage, here are three observations for the near future.

So that’s where we are. For India-US relations to turn a corner, a dramatic worsening of the US-China relationship or a change in US leadership would be necessary. Until then, it’s going to be a grind. P.S.: On the same day that Trump dropped his TruthSocial bomb, the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) Mission was successfully launched. This was the first time the two countries cooperated on hardware development for an Earth-observing mission. But this news was completely drowned out by Trump’s takedown. India Policy Watch #1: Canary in the Coal Mine?Insights on current policy issues in India—RSJIt is difficult to talk about anything other than tariffs in a week when Trump went on a tirade against India’s tariff rates, its “obnoxious” non-monetary trade barriers, and its purchase of military equipment and oil from Russia. He promised a 25 per cent tariff and an additional undisclosed penalty on Indian imports for these alleged crimes. In subsequent posts, he called the Russian and Indian economies “dead”, and rounded off what he might consider a satisfying night of posts by taunting India with some bizarre reference to drilling for oil in Pakistan. Despite all my desire to avoid reacting to random Trump provocations, it is difficult not to write about this immediate setback to the India-US trade deal that was in the works since April. But I will desist. I will give it another week and then think about writing on it. Maybe things will get clearer then. Instead, let me examine the Q1 results and commentary from corporate India and ask what we can learn about the broader state of the economy. First, there is an urban demand problem showing up in numbers. Rural demand isn’t great either, but it seems to be holding up a bit. The Kharif crop sowing numbers are up by about 4 per cent over last year, so rural demand may also continue to hold up in the remaining part of the year. But urban demand is tepid, and this was evident across the board in sectors as diverse as auto, real estate, FMCG, quick service restaurants and hospitality. What worried me more was the SBI Cards results. Now this is the largest credit card issuer in the country and the larger share of its customers belong to the “mass affluent” segment. This is in contrast to other large credit card issuers who focus on the affluent or premium segments. SBI Cards reported quite poor numbers with their card delinquency rate upward of 9 per cent. This is about 300 bps higher than the historic average and suggests significant stress among its customers to pay off their credit card dues. This might be an isolated result, and maybe we shouldn’t read too much into it. However, reading it in tandem with other results points to urban consumer stress. Now Q1 is usually a weak quarter, and there’s always a hope that as the festive season sets in Q3, the consumption demand will show up. But the general sentiment in the various commentaries I read seemed to suggest a weaker consumer sentiment than before. This surprised me because two significant measures in Q4 (Jan-Feb-March) should have helped consumer sentiment. We had a tax break for the salaried class in the budget that totalled almost ₹1 lakh crore, which was supposed to show up in higher disposable income and spur consumers to go out and spend more during the year. Also, since February, the RBI has pursued a policy of easier liquidity after a year of keeping it tight and also cut repo rates by a cumulative 100 bps to stimulate credit demand. Both these measures were targeted to get consumption going. When seen in this light, the Q1 results and the commentary suggest the consumer is still waiting on the sidelines. Why? I think the real wage growth has stagnated, private capex remains low, and consumers aren’t keen on spending or taking credit risks because they aren’t too sure about their future. The problem with discourse in India is that there’s so much noise about what the top 1-2 per cent of the income class does (high-end property registrations, luxury car sales, newer brands of boutique gins, whatever) that it drowns out any sober analysis of overall demand. There is still a lot of hope pinned on the trickle-down effect of rate cuts and surplus liquidity helping credit growth in the remaining part of the year. I remain somewhat sanguine about that thesis. Second, there is a cloud hanging over two sectors that have been particularly strong for India after COVID-19. Most of the commentary and direction from IT services companies suggested a weak demand outlook in their primary markets leading to delayed decisions or cut in IT spends. This doesn’t look like a great year for India IT services, and given its size, that has a direct impact on urban consumption. Also, while most of these companies put up a brave face on the power of AI and how they are starting to ride that wave, there wasn’t any direction on the size of the pipeline of such work. Instead, the impact of AI on automating the routine coding, developing and testing work is becoming increasingly clear. The recent news of TCS laying off mid-level employees because it wants to be a “future-ready organisation” deploying AI at scale and “realigning its workforce model” is possibly an indicator of things to come. To me, that sounds like corporate-speak for AI making an impact on their business model. I have spent some more time since I last sat around in various discussions on AI use cases that are live in organisations. I’m further convinced that coding and testing automation will be the fastest-growing use case in this area, and it won’t be IT services companies that will be quick to adopt it. Their business model relies on people deployed and hours billed, which goes against the notion of widespread automation to support clients. Rather, it will be their clients in sectors like financial services, retail, telecom, etc, who will find it remarkably easier to train their in-house team to adopt these tools. It is possible that widespread adoption of AI will lead to a new service line emerging that the Indian IT service sector will ride. But that possibility (which to me is remote) will emerge only after a serious disruption in their business model has played out. The other commentary that caught my eye was about the SME segment. This has been a bright spot for India as China+1 has played out gradually across the manufacturing sector. Since 2022, most large banks and NBFCs have reported an upward of 20 per cent CAGR of loan book growth in this segment on the back of SMEs expanding their export footprint, being hungry for working capital loans and expanding capacity. The book also remained remarkably resilient so far with net credit losses remaining below historical averages. A similar story played out in the MFI (microfinance) sector with robust growth and good quality books for most of the past 3 years. Since October last year, this story started to unravel with strain showing up in the MFI segment, which has only accelerated in the past two quarters. Q1 data shows there is now stress across the MFI sector in most of the states which has prompted the usual political moves of state governments barring financial institutions from collecting the dues (Karnataka and TN have passed laws on this). Yet, the SME sector was still going strong. Except Q1 showed signs of worry here too. Multiple NBFCs, most notably Bajaj Finance, the largest among them, called out stress they see across the board among SMEs. NBFCs are the largest lenders to this segment, filling up a gap left by universal banks because of a historical regulatory arbitrage that has somewhat evened out in the past few years. This SME segment stress seen by NBFCs could be a temporary blip, but loans don’t go bad immediately, and most banks and NBFCs have a good set of lead indicators that give them a sense of how things will pan out for at least 2-3 forward quarters. Since they have called it out, my sense is we are at the beginning of a credit cycle in this segment for NBFCs. We will see credit drying up here as underwriting norms tighten to address this incipient stress. The 20+ per cent CAGR growth days might be ending here. The possible medium-term upside here is the FTAs that India has (almost) concluded with the EU and UK. Notwithstanding Trump’s randomness, India should do its best to conclude the trade deal with the US and close others in the pipeline too. The SME segment has shown in the past 4 years that they have it in them to compete globally, despite the limited progress we have made on deregulations to help them. Lastly, the inflation print for June came in at a 77-month low of 2.1 per cent. This means there’s more room for RBI to cut rates and my guess is if we continue to have inflation in sub 3 percent range and consumption remains weak, we will see one as early as October. But like I have mentioned above, the core thesis of rate cuts and injecting liquidity remains that the credit growth weakness is on account of supply of credit. I think this is partly true. Demand weakness is a reason too. Corporate credit growth is no longer dependent on repo rates as it used to be in the past. Most large corporations are at their lowest leverage ratios in the past two decades and their operating cash flows are higher than investing cash flows. The equity markets, which is where household savings are increasingly flowing, are still buoyant which is keeping equity capital cheap for corporations. The bond market continues to be strong and there’s private credit also available. So, Bank loan rates are no longer a determinant for corporate credit needs. On retail credit, the credit bureau data suggests that the rate cuts and liquidity infused so far haven’t led to higher enquiries for loans. Maybe there’s a threshold after which the demand will show up. I still think the underlying sentiment is weak, which means even if there’s a supply of credit, the demand won’t pick up. Also, the signs of stress in SME and the existing stress in MFI and unsecured loans will lead to higher caution among lenders. All of the above indicate we might soon have a situation where financial institutions have excess liquidity with limited opportunities to deploy which is a different problem to contend with. But that’s a distinct possibility. The way out of this is to navigate through the tariff wars with FTAs and concessions to key trading partners on our tariff rates and non-monetary barriers. This is a good time to make a case for it to the domestic constituency that likes the support of tariff barriers. The other long-pending area is to focus on deregulation on a war footing. There’s been a statement of intent on this in the past year or so, but with insufficient follow-through. That remains the single biggest ‘unlock’ for growth if done with speed and purpose. India Policy Watch #2: City of JoyridesInsights on current policy issues in India—Pranay KotasthaneI spent most of my week in Kolkata as a tourist, visiting the city’s iconic sights and food establishments. I had gone there to speak at The Conversation Room on all things public policy over great food and beer, a perfect setting to discuss the Indian State and its predicaments. Because what Oscar Wilde said about life—”Life is too important to be taken seriously"—applies equally to public policy. All first-time visitors to a new city instinctively start comparing the likeness and differences with the city where they live. And because the Indian State’s omniabsence is unmistakable, the causes of city differences and likeness are often related to public policies. So here’s one such account. The policy domain that struck me most was how Kolkata and Bengaluru handle urban transport. Of course, the most striking urban transport similarity between Kolkata and Bangalore is traffic jams everywhere. Travel times are high in both cities. The root causes, however, are pretty different. In Bengaluru, poor road design, potholes, wrong-side driving, and ill-maintained trunk roads are the main culprits. Conversely, in Kolkata, while trunk roads are generally well designed, the sheer diversity of vehicles and lack of technology like synchronised traffic signals seem to be the main reasons for the congestion. The presence of traffic police on Kolkata’s streets was an order of magnitude higher than in Bengaluru, but there’s only as much they could do without automated traffic flow handling. Now the differences. For someone coming from Bangalore, the diversity of vehicles in Kolkata is immediately noticeable. Kolkata has a metro system (India’s oldest), local trains, ferry services, e-rickshaws (colloquially called Totos), flag-down taxis, bike taxis, all the major ride-sharing cab aggregators, along with Uber Shuttle, private buses, and government buses. There’s also the colonial-era tram service, which now runs limited services on two routes and will wither away soon. On the outskirts, one can see autos (but plying as fixed-route shared transport) and the manually-propelled cycle rickshaws. This range of transport options available is quite remarkable compared to Bangalore's more limited choices. Given West Bengal’s politics, I had imagined a government-run monopoly over Kolkata’s public transport. But I was wrong. In Kolkata, I found three kinds of buses operating—government-run and government-operated buses, government-owned but privately-operated buses, and entirely private buses permitted to run on major routes. The state-run West Bengal Transport Corporation (WBTC) website acknowledges the role private buses play as follows:

This contrasts sharply with Bangalore's BMTC monopoly, which is protected by not issuing stage carriage permits to private operators. This kind of permit allows buses to pick up and drop off passengers at different stops along a route, unlike a contract carriage permit, which only allows point-to-point operations. As a result, the only urban transport conversation in Bengaluru is about the number of buses BMTC can buy and put on the roads rather than about opening this sector to competition from private players. Of course, there are challenges with allowing private buses to operate. But public policy often involves making second-best choices. You can either have a small, reasonably well-run government-only bus system like in Bengaluru, which keeps failing to meet a city's growing demands. Or you could have numerous cheap shared transport options, albeit not always of the highest quality, like Kolkata does. Another difference is that Uber Shuttle is allowed in Kolkata but not in Bangalore for the same reasons as above. Successive Karnataka governments have been protecting a state-run monopoly at the cost of everyone else. Similarly, bike-taxis operate in Kolkata but are no longer allowed in Bengaluru. Regarding cab aggregators, it was interesting to note that Kolkata takes a more liberal approach to prices than Bangalore. Kolkata allows for capped surge pricing. Through a 2022 notification, cab aggregators can charge a fare 50 per cent lower than the base fare and a maximum surge pricing of 50 per cent above the base fare. Ride pooling is also allowed. In Bangalore, on the other hand, the state government has banned surge pricing, allowing charges in bands depending on the price of the vehicle. Nor is ride pooling permitted. These contrasts highlight that running a big urban centre well requires governments to make practical choices even if they don’t fit neatly into political ideologies. All our cities need better urban transport, but Kolkata already has many building blocks of urban transport. This wasn’t something I had expected as a tourist in the City of Joy. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

|