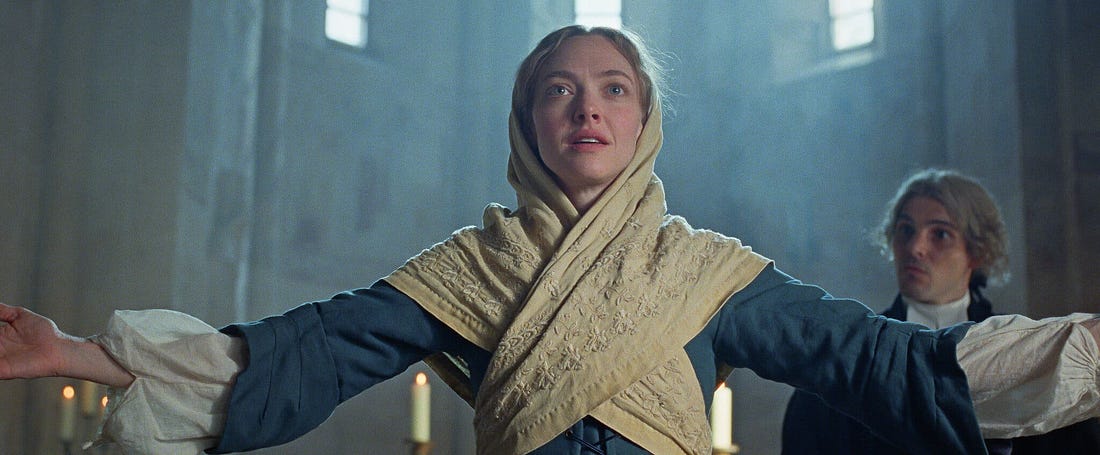

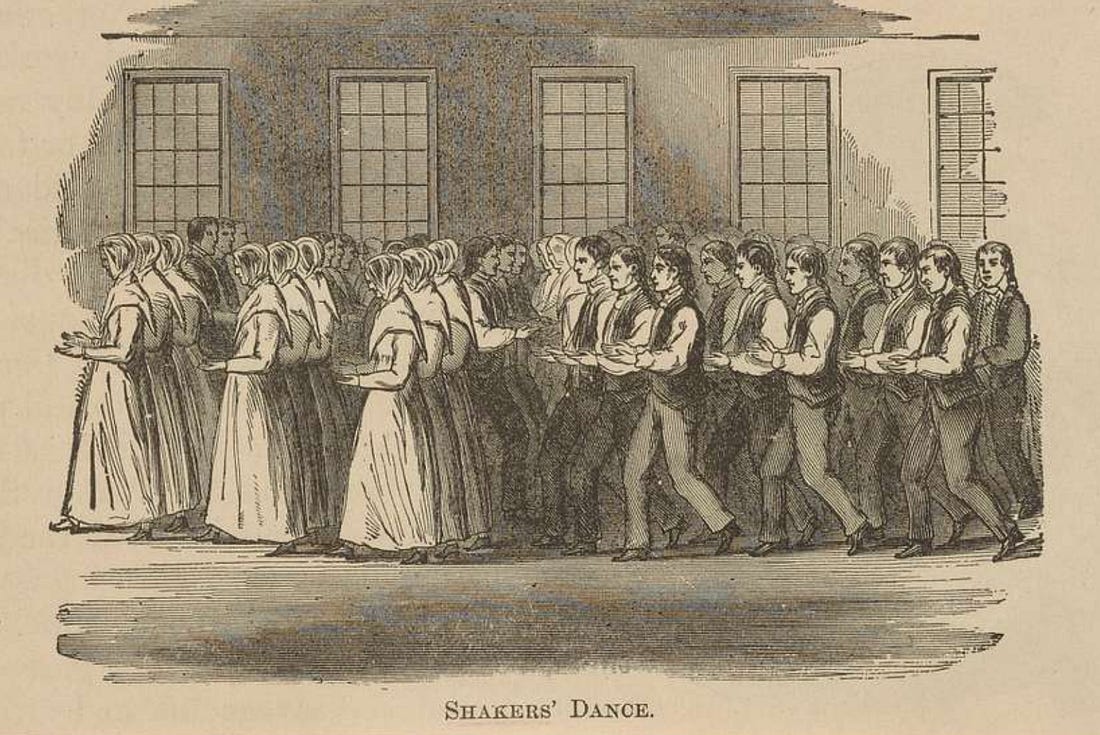

A couple weeks ago I saw The Testament of Ann Lee, directed by the Norwegian filmmaker Mona Fastvold and starring Amanda Seyfried, in an extraordinary performance. The film traces the life of Ann Lee, known to her followers as Mother Ann, the founder of the Shakers—and widely regarded as the first woman to establish and lead a durable, institutional religious movement on American soil, one that has endured for more than two centuries. Rather than presenting her as a saintly exception, the film approaches her as the catalyst for a way of life that fused belief, discipline, and collective form. My own fascination with the Shakers long predates this film, and has always surprised me, given that I am a non-believing heathen. In the years following 9/11, I found myself searching—perhaps instinctively—for an aspect of U.S. culture that offered grounding and moral coherence without triumphalism. My almost accidental recollection of the Shaker song “Simple Gifts” arrived as something like a personal revelation: here was a society that had forged, through its own pathways of faith, a spiritual cosmology in which community, morality, and the self were not in conflict but in alignment—values rendered tangible through visual culture, choreography, music, and disciplined daily practice. It is precisely this centrality of music that made the film’s promotion as a “musical” give me pause. I braced myself for a campy, Broadway-style treatment—something closer to The Book of Mormon than to the severe spiritual economy the Shakers practiced. Thankfully, Fastvold avoids this trap. The film draws instead on authentic Shaker songs and hymns, subtly adapted to meet the demands of contemporary cinema without betraying their origins. In doing so, it constructs a careful bridge between the radical austerity of a cappella worship and the expressive requirements of a twenty-first-century cinematic language. What emerges through this attention to form is not only a portrait of belief, but of endurance. The Shakers were persecuted and condemned for their ideas, yet remained steadfast in their commitments. Perhaps unconsciously—not only because I have a weakness for antiheroes—I instinctively saw in them a figure for the artist: someone who persists in pursuing a singular vision against ridicule, hostility, and misunderstanding, sustained not by certainty or reward, but by a faith in the necessity of the work itself. The reason the Shakers became philosophically relevant to me when I first began researching them—and the even stronger reason they feel urgent now—has to do with the radical social commitments that structured their faith. They were uncompromising advocates of the equality of the sexes; they were abolitionists, with several Black Shakers counted among their members; and, most consequentially, they were pacifists. This last position repeatedly placed them in direct conflict with the federal government. The harassment, physical violence, and imprisonment that Ann Lee and her followers endured (which are dramatized, yet accurately portrayed in the film) were not incidental episodes of intolerance, but the predictable consequences of their refusal to compromise on these principles. Their persecution was the price of consistency. What makes their example especially resonant in the present moment is precisely this coherence between belief and action. At a time when American evangelical movements have yet to fully reckon with the contradictions of a political theology that claims to hold human life as sacred in debates over abortion, while simultaneously endorsing state-sanctioned violence in the name of border enforcement, the Shakers offer a stark counterexample. Their faith did not permit selective ethics. It demanded a moral logic that applied universally, even when doing so incurred punishment. In that sense, their relevance today lies less in their theology than in their insistence that ethical principles, once professed, must be lived without exception. Seen from the present, the film also invites reflection on how entire communities come to organize themselves around charismatic authority. The devotion inspired by Ann Lee reminds us that belief often operates less as private conviction than as a shared social force, sustained through ritual, repetition, and collective affect. Yet the ethical stakes of such devotion vary dramatically. In the Shaker case, authority bound belief to discipline, restraint, and consistency, asking followers to accept sacrifice—and even persecution—as the price of fidelity to their principles. Many contemporary movements animated by religious or quasi-religious fervor, by contrast, mobilize intense loyalty without imposing comparable ethical demands, allowing allegiance to substitute for coherence. The distinction that matters here is not belief versus unbelief, but whether collective faith functions as a discipline of responsibility, or instead as a structure that exempts power from moral accountability. What distinguishes the Shakers is not that they refused to derive ethics from belief, but the particular way in which belief was structured as practice. Their radical pacifism was not a secular moral position, nor an independent ethical philosophy; it was a direct expression of Shaker theology, a religious obligation rooted in their understanding of divine love, communal discipline, and the imitation of Christ’s spirit. Violence was rejected not because ethics had been abstracted from faith, but because faith itself demanded a form of life organized around restraint, care, and non-domination. The lesson of that distant period in American history for those of us working in the cultural sector or engaged in activism is not that we need to subscribe to an organized religion, but that ethical and political life still requires something like faith: a durable commitment to one another that involves risk, sacrifice, and endurance. This is the terrain that Simon Critchley maps in his book The Faith of the Faithless, where faith is not proposed as the source of ethics, but diagnosed as the form through which responsibility persists after belief has fractured. Whether grounded in religion or not, the moral question of violence cannot be fully absorbed by doctrine, institution, or ideology. It remains, finally, a burden borne by persons and communities in practice rather than in principle. As someone who emigrated to the United States, I have often felt out of place. Yet from the beginning I also recognized—and deeply valued—what seemed to me an innate cultural trait here: a respect for individual opinion. That respect is not a matter of politeness or tolerance alone; it is a cornerstone of democratic life and a fundamental mode of recognizing another’s humanity. To be heard, even when one is wrong or marginal, is to be acknowledged as a moral subject. I still believe this country retains that capacity. Like any society, it is vulnerable to fanaticism and to the seductions of false prophets, but it is not irredeemably defined by them. Its goodness lies precisely in its ability to recover—through dissent, self-critique, and renewed commitment to shared principles. Helping it do so is not the task of belief alone, but of work: collective, imperfect, and sustained. In that sense, the responsibility to repair democratic life belongs to all of us, and especially to those who labor in culture, education, and the public imagination. Simple Gifts, which was the song that led me to this lifelong research and appreciation of the shakers, perfectly encapsulates that search, with humility and discipline: When true simplicity is gained, Invite your friends and earn rewardsIf you enjoy Beautiful Eccentrics, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe. |