While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. If you enjoy what’s written here, you will also like our book, Missing in Action: Why You Should Care About Public Policy. #283 History MakersTaking Stock of 2024 Predictions, Honouring India's Great Sons, and American Policy Self-goals—US Steel Version.Happy New Year— RSJHappy 2025, dear readers. 2024 and everything good and bad that it brought is behind us. May the new year be filled with hope, happiness and prosperity for all of you. We had a boring, normal 2024 ourselves. Pranay had a wonderful book - We, the Citizens - out during the year, which you must buy if you haven’t. The newsletter kept chugging along (we did the usual 44 editions during the year), as did the world around us despite the occasional minor threats of a third world war. The usual way for me to begin the opening edition of any year is to look back at the predictions I had made for the year gone by and how I fared. I will follow that tradition this year too. But before I do that, there are a few homages to pay. India lost three extraordinary personalities in the last fortnight of 2024. For me, a child of India of the late 80s and 90s, these losses were personal. Shyam Benegal arrived on the Hindi film scene when the genre of ‘masala’ Bollywood movies was taking root. Through the 80s and 90s, Benegal resolutely carved his own path in parallel to the mainstream. He was hardworking and prolific, meaning there was a Benegal film every other year. He discovered talent and nurtured them. The finest of acting talent in India in the past half a century is a product of the Benegal school—Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Om Puri, Smitha Patil, Amrish Puri, Girish Karnad, Anant Nag—the list is endless. It wasn’t the actors alone. The list of technicians who were part of Team Benegal is longer and perhaps more impressive. Govind Nihalani, Ashok Mehta, Satyadev Dubey, Vanaraj Bhatia—people tremendous in their craft who would make a name for themselves. Benegal films and his equally seminal work for television came to me through Doordarshan, the state-run monopoly that was my only window to the world outside. He was the most Indian of directors dealing with subjects from the lives around us in a cinematic language that was spare, real, but always accessible. Feudal oppression in villages (Ankur), casteism (Nishant), sexual violence (Mandi), co-operative movement (Manthan), history of India (Bharat Ek Khoj, Junoon), license raj (Kalyug), early Indian cinema (Bhumika), the lost art of storytelling (Suraj Ka Satwaan Ghoda), partition (Mammo), royalty (Zubaida), Gandhi (The Making of Mahatma), railway travel (Yatra), Constitution (Samvidhan), elections (Welcome to Sajjanpur), Bose—the range of his work is mind-boggling. He was my window to how ordinary Indians lived and breathed. His films examined our society and how we came to be the way we were in a manner that was both meaningful and entertaining. Those films are among the most clear-eyed documentation of India of the past hundred years. There are public policy lessons galore in them. He was an institution. Quite literally for me. In edition #26, I had this to say about Benegal’s Kalyug.

RIP, Shyam Babu. We also lost Zakir Hussain in this period. Zakir was a tabla maestro, an Ustaad, in the real meaning of that term. But he was much more. To us, growing up, he was an electric presence on screen and stage who blended the traditional and the modern India within him. He was equally at ease in a jugalbandi with Hariprasad Chaurasia as he jammed with the Grateful Dead or was the beating heart of the Mahavishnu Orchestra and Shakti. He stood for the India that we often espouse for in these pages - self-confident, rooted in tradition and open to the world. Shruti Rajagopalan has this beautiful piece that captures the essence of Zakir Hussain and what he meant to so many of us. Gone too soon. Going back to that old edition that spoke of Kalyug and License Raj, here’s another extract from it:

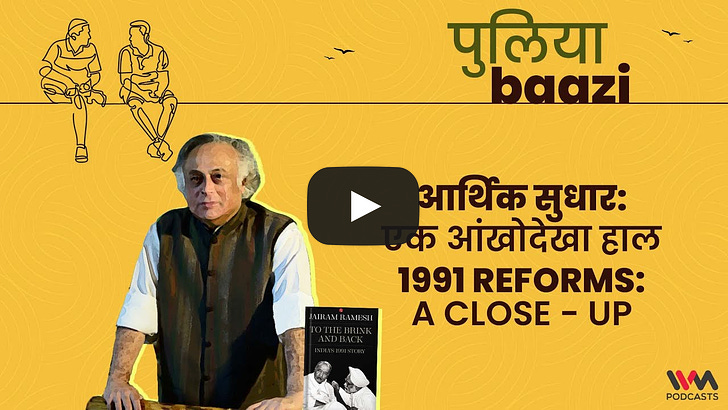

That dismantler of license raj too passed away in the last week of December 2024. A lot has been written about Dr. Manmohan Singh. And there’s good quality documentation of the 1991 reforms that has been done in the past few years. Those reforms weren’t an overnight effort. There wasn’t a single individual who led those reforms. It took time, possibly a decade or more, for those initial reforms to play out in terms of impact. Yet, I’m convinced if the face of those reforms wasn’t a gentle, soft-spoken, erudite Sardar who rose from poverty and the horrors of partition to walk the halls of Oxbridge colleges and the United Nations as a scholar economist, it wouldn’t have been as successful. He changed our lives. He changed mine for sure. He was quite prescient when he remarked at the end of his prime ministerial tenure that history would judge him more kindly. He was a hero of our time. He was hero of mine. Onwards to how I fared on my ten 2024 predictions. I have edited the predictions to keep them concise.

Biden should have stepped down in February if he wanted his party to have a fighting chance. He did it instead in July, and the Democrats’ goose was well and truly cooked. Trump, as I predicted, would have won regardless of who Democrats put up. The only point of discussion was the margin of the victory.

I got that wrong. The deficit continued to balloon, and the Fed did cut rates at the back end of the year a bit too aggressively, but the hard landing didn’t come. It is only a postponement in my view because this level of deficit isn’t sustainable.

Pretty much spot on, including a predicted fiscal package. China did wow the world with the progress it continues to make in green tech and, increasingly, in AI and quantum computing. None of it will help with the immediate problems of low demand, high debt, and a deflating economy.

Well, my prediction was that the BJP would end up with about 260-270 seats. They fared worse and ended up at 242. But broadly, I was right when I predicted this back in the first week of January 2024. The surprising underperformance stopped PM Modi from ushering in the generational change in the cabinet. I expect it to happen in 2025-26.

As I write this, the Dollar is at a two-year high. I got this completely wrong.

She didn’t scalp a really big one but FTC did make life of Big Tech more difficult in 2024. And there was the FTC's landmark antitrust case against Google, where the federal judge called out Google for abusing its dominant position in the search business. At the end of the year, the FTC blocked the mega-merger between grocery chain Kroger and Albertsons for reasons I’m still trying to understand.

Pretty much on target of 6,5 per cent growth, but inflation was closer to 5 per cent for the full year. Net FII inflow was the lowest in many years, and Nifty was up by 8.5 per cent. Not great, but not bad either.

That’s how it went. No real fighting has been going on in Gaza for more than six months now. The Hezbollah leadership has been decimated, and Iran is licking its wounds. The Russia-Ukraine war is a battle of attrition that’s ongoing, and it will take a Trump-Putin summit to settle.

Both didn’t happen. Novo Nordisk fell through the year after hitting a high in March. Nvidia was the real story.

Well, this is precisely what happened with ONOE. So that went exactly as predicted. Overall, the prediction scorecard is about 6/10 or maybe 7/10 if I were being generous. On to 2025 predictions in the next edition. Happy New Year once again. India Policy Watch: “In Dealing With the Affairs of the State one Should be Full of Sentiment but Never be Sentimental”Insights on current policy issues in India— Pranay KotasthaneJust as India’s independence was the defining macro-event of people from my grandfather’s generation, the 1991 economic independence was the defining macro-event of my generation. Some still consider the 1991 reforms a high-falutin change that only impacted a few wealthy people. But if you ponder hard enough, you’ll realise that these reforms had a long-lasting impact on all of us. I was six years old when the reforms happened. At the time, my Dad worked as a laboratory chemist in a private fertiliser company’s office in Indore. The reforms had a profound impact on us. By 1991, the fertiliser subsidy had grown to be the single-largest in the government budget. That’s because the prices of fertilisers were controlled, and since July 1981, there had been a zero per cent increase in fertiliser prices even as the government kept increasing crop procurement prices. As a result, the government’s fertiliser subsidy bill kept ballooning. This subsidy was paid to fertiliser companies according to the government’s whim. With the fiscal crisis approaching, there was a real threat that the government could default on these payments. All companies hunkered down. The 1991 reforms didn’t dismantle this regime but introduced some significant changes. The government raised fertiliser prices by 40 per cent on average (later reduced to 30 per cent) and introduced a ceiling on the subsidy paid on certain phosphate fertilisers. At the same time, the reduced licensing requirements made it easier for companies to expand production capacity and modernise facilities. The gradual reduction in import duties on raw materials like phosphoric acid helped fertiliser producers access key inputs at better prices. The increase in fertiliser prices initially led to a reduced demand, leading companies to consolidate. The laboratory where my Dad worked was closed down in 1992. At the same time, a reduction in licensing requirements allowed the company to focus on expanding its manufacturing facility in Goa. So, my Dad was asked to move to Goa—a place he and the family had zero idea about. My parents took the chance. I count this move to a new place with a diverse, liberal culture as the best thing that could have happened to the seven-year-old me and my younger sibling. Soon after the licensing requirements were dismantled, the company’s sales turnover increased. By 1994-95, it had doubled its capital deployment. The profits increased. Personally, all this meant that my Dad had a stable job at that company for over three decades, allowing my parents to invest in our education and helping us become responsible citizens. The 1991 reforms were deeply personal. Like my story, I’m sure they intersect with your life trajectories. We must thank many reformers who played their part in steering the Indian economy away from rotten socialism, none more than Dr Manmohan Singh. Without him, India would have settled for some lame debt restructuring programme of the kind that Pakistan routinely does to this day. The political support for using the crisis to overhaul India’s economy was weak, even within the ruling party. Had it not been for his conviction, expertise, and advocacy, the crisis would have gone to waste—as it often does. I think the best tribute to him is reading through his speeches and responses in the parliament between 1991 and 1995. Thankfully, the Parliament’s Digital Library Project has made it easier to locate these discussions. Let me point to a few highlights. His combative response in the Rajya Sabha terming the opposition to rupee devaluation as anti-national:

The legendary lines that ended the 1991 Budget speech:

And the emotional lines at the end of the 1992 Budget Speech:

Global Policy Watch: Steeling DownInsights on global issues relevant to India— Pranay KotasthaneOver the last two editions, I’ve been trying to make sense of American policy self-goals. I argued that the US is deploying the same policy instruments that one would typically associate with China. In doing so, it’s playing to the adversary’s strengths instead of its own. As if to dig a deeper hole for itself, the American president blocked Nippon Steel’s acquisition of U. S. Steel earlier this week, citing vague national security concerns. In his words:

Further, there seems to be a bipartisan consensus on this issue. President-elect Trump had also made clear his opposition to the deal. In other words, the US believes it’s alright to block a Japanese company from investing in a commodity firm on national security grounds. Observe the geopolitical signals that this move sends. First, this is the first time that the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) has blocked a deal that does not have Chinese ownership issues. Blocking a company from a friendly country on ill-explained national security grounds marks a disturbing change in America’s geoeconomic approach. Hitherto, the stated approach of the US towards China was termed “small yard, high fence”, meaning that in a narrow set of advanced technologies, Chinese firms will be resisted with the full force of the American State. In other areas, the approach will be business-as-usual. By blocking a takeover from a company of an ally country, the government has adopted a “huge yard, very high fence” approach instead. This will have a chilling effect on partner countries. The second issue concerns the product at hand—steel. To raise the national security red flag for an industrial-age product with multiple global suppliers seems comical and anachronistic. U.S. Steel is the third-largest steel producer in the US. The Department of Defense (DoD) purchases zero per cent of its output. In fact, the Pentagon’s demand accounts for less than 1 per cent of the entire American steel industry’s output. Thus, it is difficult to understand how this acquisition would have adversely impacted American national security. The third—and perhaps the most important issue from an Indian perspective—is what this move reveals about the American state of mind. It strengthens the narrative that recent American governments seem to be acting against all America has stood for. Instead of chutzpah and boldness, the move symbolises fear, defensiveness, and nervousness. Not a good signal to send to your partners and allies. What’s also concerning is that despite abundant knowledge and state capacity, the US seems to be making such policy blunders. In this case, too, most mainstream think tanks across the board were supportive of the acquisition. And yet, the government thought otherwise. There seems to be a major flaw in the American policy pipeline. HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :). If public policy interests you, consider taking up Takshashila’s public policy courses, specially designed for working professionals. Our top 5 editions thus far:

|