Reminder: We’ve launched The Ladder from The Ankler, a members-only hub for early-career professionals. For more information or to apply, click here. Our first event is coming Nov. 3 in Brooklyn with The Cramer Comedy Newsletter. Vampira, Elvira and the Epic Battle Between Two L.A. Horror QueensA bitter lawsuit, black wigs and major money (for one): The town wasn't big enough for two strivers cut from the same goth

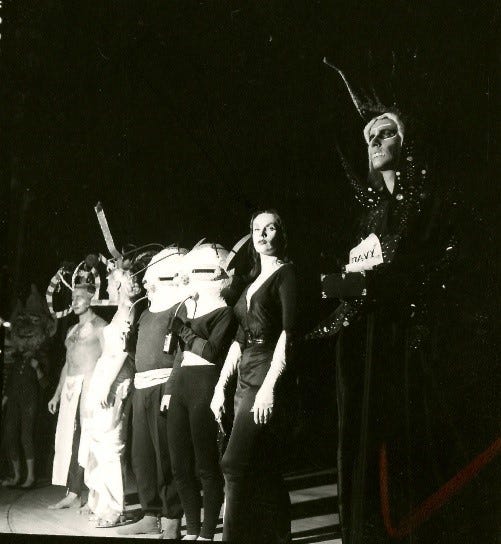

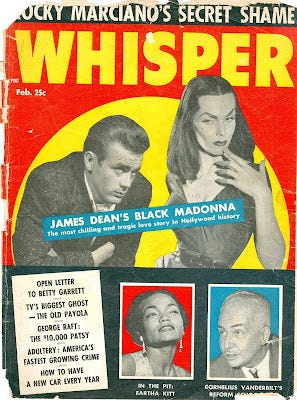

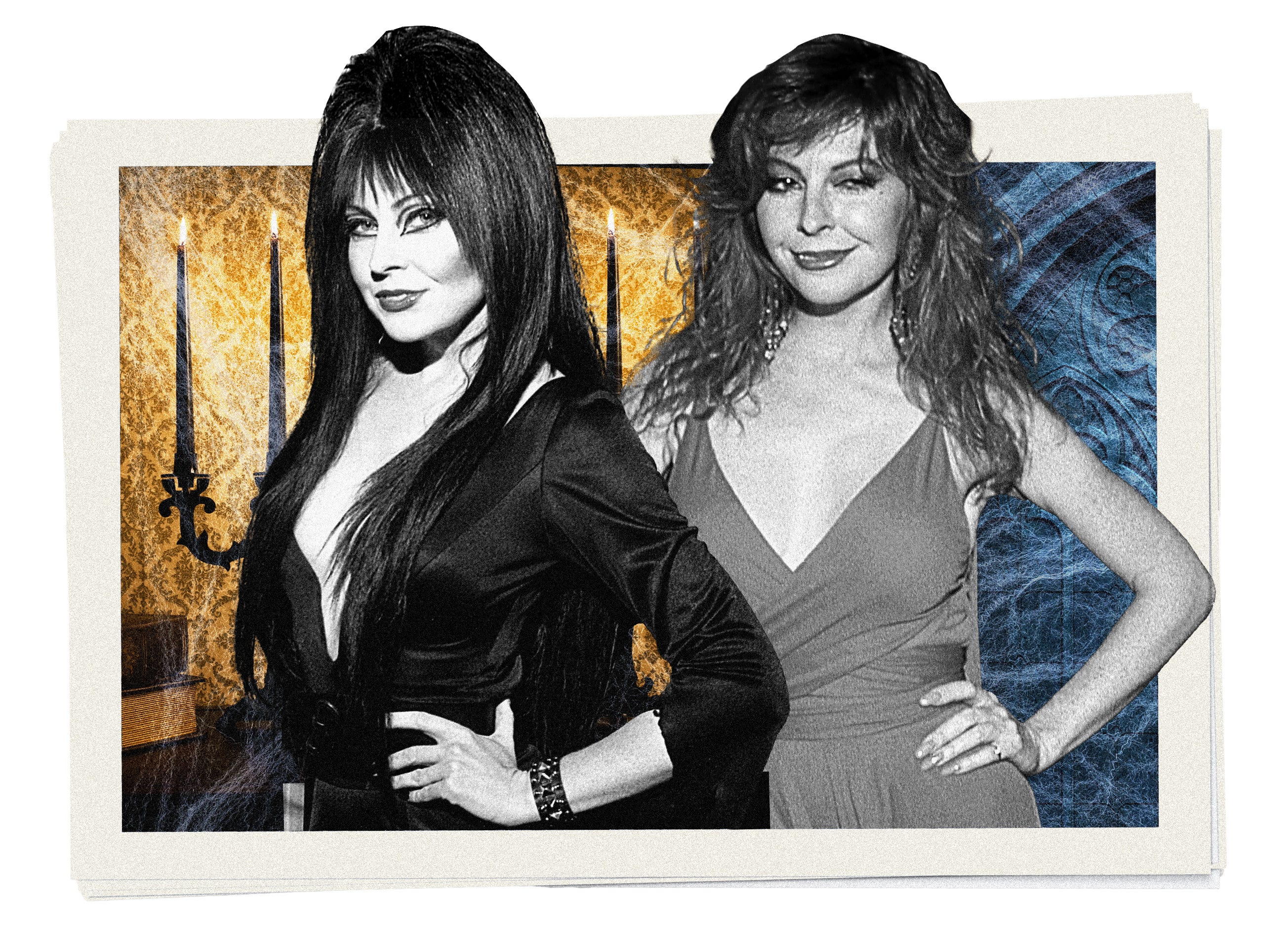

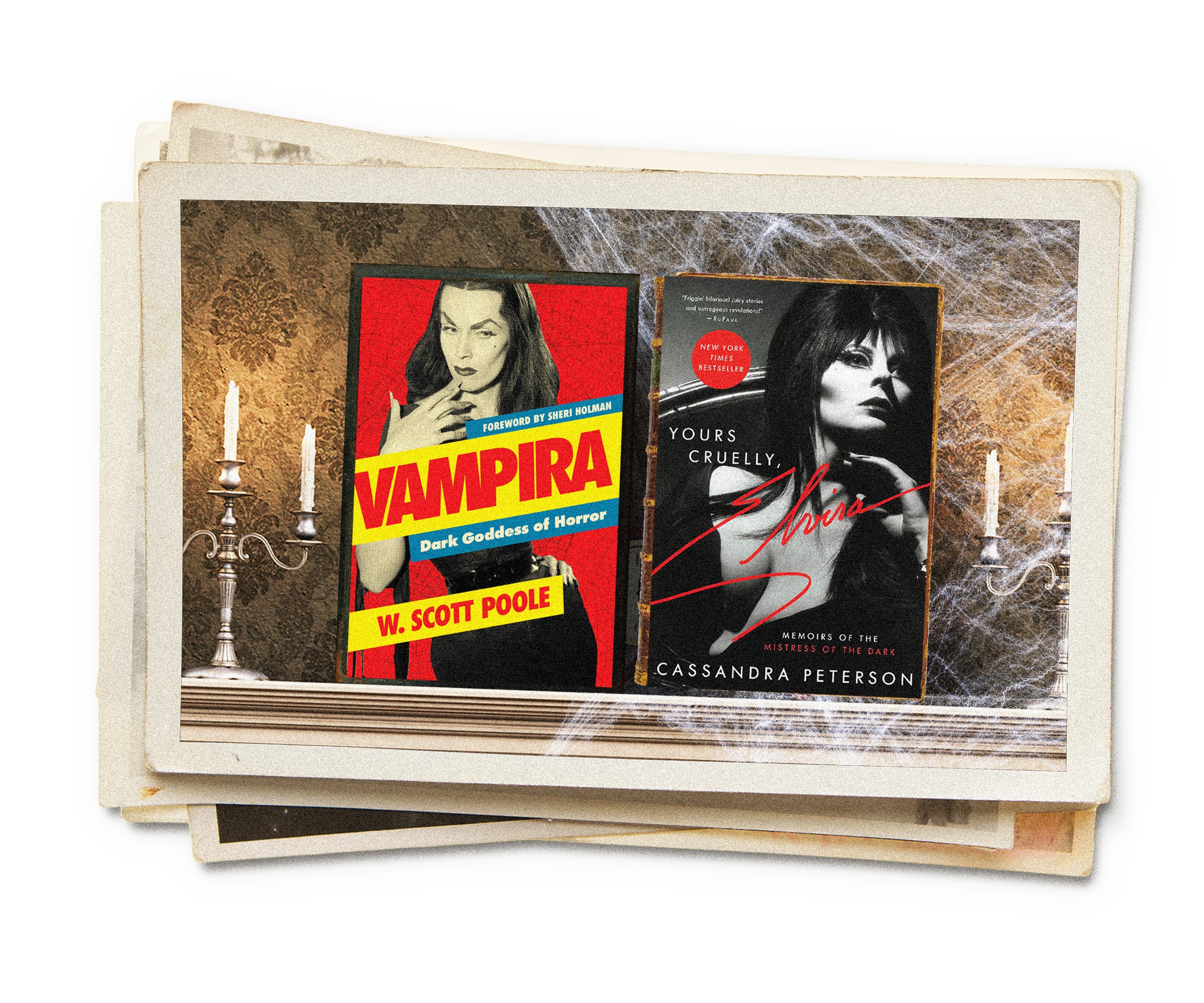

Joe Pompeo writes about Hollywood history every other Saturday. He recently revisited Al Pacino’s role in Dog Day Afternoon, Rudolph Valentino’s 15 Days of Tawdry, Tabloid Death, and Marilyn Monroe’s Overdose and the Echo in Matthew Perry’s. You can email him at joepompeo@substack.com or sign up for his personal Substack.Just before Halloween in 1987, a fluffy USA Network program called Hollywood Insider aired a segment on Cassandra Peterson, better known as Elvira, Mistress of the Dark. Peterson, then 36, had shot to stardom six years earlier as the host of Elvira’s Movie Macabre, a syndicated b-movie schlock fest created by L.A.’s KHJ Channel 9. Movie Macabre launched Peterson into something much more formidable than a sex-kitten horror character with cult appeal. “You’re looking at a woman who has created her own industry,” gushed Hollywood Insider’s Sandie Newton. “There are Elvira greeting cards, Elvira makeup products, Elvira comic books, Elvira t-shirts — enough stuff to make a virtual shrine to tackiness.” On the horizon loomed a feature film, a Marvel comic strip, and a potential sitcom for NBC, where Elvira was due to appear on Saturday Night Live’s Halloween special a few days later. Peterson was also developing an Elvira cartoon show, and she’d inked a contract for Elvira to shill beer on behalf of Coors. “Before Elvira, Cassandra Peterson ran the gamut of performing gigs,” Newton continued. “She was a showgirl in Las Vegas, and she had a bit part in a Fellini movie. But then she attended an open audition here in Hollywood for the part of Elvira. Her good looks and her comedy skills got her the job, and the reward has been the fame and the money from all the Elvira merchandise.” Peterson chimed in. “We jumped on the bandwagon and really went to town with the merchandise,” she said, adding with a laugh, “which is a perfect thing for Elvira, because she’s, you know, she has no morals or anything.”  As viewers lapped up Hollywood Insider’s Elvira interview, 65-year-old Maila Nurmi seethed with bitterness in her tiny Hollywood apartment. Nurmi herself was a gothic pop icon, but her career had long since tanked. She now lived in penury, barely squeaking by on Social Security benefits. It was a far cry from her glory days as America’s original horror host, Vampira, created by Nurmi for KABC Channel 7 — a worldwide phenomenon for two brief but bewitching years in the mid-1950s. Back then, Nurmi was at what would be the height of her career, a trailblazing sex symbol and subversive cultural rebel who cast a spell on postwar America at the dawn of television and rock ‘n’ roll. She’d been nominated for an Emmy. She’d forged a deep but ill-fated friendship with James Dean. She’d performed with Liberace, shared a memorable moment with Elvis Presley — and inspired the look of Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty. Then it all came crashing down and Nurmi faded into obscurity, another forgotten figure on the long list of Hollywood washups. “Nurmi would spend most of her life seeking stardom in L.A.,” W. Scott Poole observes in his 2014 biography, Vampira: Dark Goddess of Horror. “Like tens of thousands of others, she never succeeded. But unlike most, she came deliciously and heartbreakingly close.” In 1981, when KHJ hatched a plan to revive Vampira, Nurmi initially got on board, agreeing to license her iconic character and join the reboot as a producer. Before long, however, the partnership went south over creative differences. That’s how Peterson, KHJ’s chosen Vampira successor, became Elvira instead, attaining fame and fortune while her struggling forerunner languished. Predictably, there was no mention of Nurmi or Vampira in the Hollywood Insider segment. But that same week, Nurmi did a media hit of her own. “The character she is playing is 75 to 80 percent Vampira — some parts are missing, some things have been added,” Nurmi told The Los Angeles Times. “They’ve taken a larger part of Vampira and added these lowly commodities and given it a wider common denominator, but in so doing this, destroyed the character. I resent their taking my product and doing that to it.” Nurmi’s resentment was hard to overstate. She was angry. She’d had enough. And by Halloween 1987, she was ready to do something about it. 'Vaguely Deathly in Tone'Born Elizabeth Maila Syrjäniemi in 1922 to Finnish immigrants who raised their family in Ohio and Oregon, Maila Nurmi, as she later renamed herself, pursued an acting career straight out of high school — first in Los Angeles, then in New York, then again in Los Angeles after being discovered by Howard Hawks. Nurmi’s association with the legendary director was short-lived, and it became apparent that the Finnish beauty would not in fact be the next Lauren Bacall. With little more to her name than a few Broadway credits and a portfolio of pin-up shoots (never mind her dalliance with Orson Welles, rumored to have resulted in a son), Nurmi was cast back into Hollywood’s vast ocean of strivers. By the early 1950s, Nurmi had wed the screenwriter Dean Riesner and moved to the Hollywood Hills, essentially living as a full-time housewife in a marriage that wouldn’t last. But fate lurked just around the bend. In Oct. 1953, Nurmi attended the annual “Bal Caribe” masquerade at L.A.’s Earl Carroll Theatre, a fundraiser hosted by the choreographer Lester Horton. Dressed for the occasion, she resembled the matriarch of The New Yorker’s popular “Addams Family” cartoons, in a tattered black gown with generous décolletage, stiletto heels and pale makeup caked on her angular face. “Everything was vaguely deathly in tone,” Nurmi would recall years later. Not only did Nurmi win the evening’s costume contest, but she caught the eye of Hunt Stromberg Jr., program director for KABC-TV (and the future CBS programming executive behind The Beverly Hillbillies, Gilligan’s Island and Green Acres). Two months after Horton’s Bal Caribe, Stromberg tracked Nurmi down and gauged her interest in hosting a late-night horror-movie show for Channel 7. It might not have been the break she’d been looking for, but it was a break, and she grabbed it. Nurmi went to work on her Morticia Addams-inspired hostess. It was her husband Riesner who came up with the name Vampira, but the visual aesthetic was all Nurmi, who looked to the fetish magazine Bizarre for inspiration: gratuitously arched eyebrows, three-inch nails, a waist squeezed so tight, according to Nurmi, that its maintenance required a two-day fast and a steambath each week before filming. Vampira was part Bride of Dracula, part Gloria Swanson circa Sunset Boulevard, with the requisite dose of camp. At a time when wholesome comedies like I Love Lucy and Leave it to Beaver tickled the masses with their chipper domesticity, Nurmi found herself drawn to Addams’ dark spin on the American dream. As Poole notes in his biography, “Vampira emerged from Nurmi’s sense of cultural rebellion rather than a simple desire to entertain. Her own experience as a failed housewife in a failing marriage encouraged her to mold a character that took the assumptions about married love, gender roles and family life then on display in popular ‘soap operas’ and turned them upside down.” The Vampira Show premiered on Apr. 30, 1954 and instantly became a cultural sensation, garnering features in Newsweek and Life within weeks of its debut. “At an hour before midnight each Saturday,” Life’s four-page spread began, “a gaunt, black-wigged mistress of ceremonies steps out of ominous, drifting mists, screams hysterically into a shuddering camera . . . and then sighs morbidly, ‘I hope you have been lucky enough to have had a horrible week.’ With this beginning the macabre lady, who calls herself Vampira, invites her audience to watch a program of choice horror films, including such scary relics as White Zombie and Fog Island. Between movie reels Vampira provides eerie interludes of her own . . . She has thrown herself wholeheartedly into her role, going abroad dead-panned and shrouded even in daytime to enlarge her horror-loving public.”  Vampira’s appeal was more than just a novelty. In Mar. 1955, Nurmi arrived at the Moulin Rouge Nightclub in an ice-blue evening gown with a rented fur stole draped over her shoulders for the 7th Annual Primetime Emmys. The Television Academy had nominated Nurmi for Most Outstanding Female Personality in the “Hollywood Achievement Awards,” which recognized excellence in local programming. She didn’t win, but just being there — an honoree among the Hollywood elite — felt like one. The following month, Nurmi’s stock soared higher when she appeared on NBC’s hit Saturday-night variety series, The George Gobel Show. A local channel in L.A. was one thing, but this was a national broadcast viewed by millions. “It was the pinnacle of her career,” wrote Nurmi’s niece, Sandra Niemi, in her own Vampira biography, Glamour Ghoul, published in 2021. “Fourteen years since she first stepped off [a] bus in Los Angeles, after endless struggles and countless rejections, she’d perform on the highest-rated show on television.”  But there was a catch: doing The George Gobel Show meant Nurmi couldn’t do her own show that Saturday. It was only for one night, but the brass at KABC were furious that Nurmi had disobeyed their instructions to decline Gobel’s invitation. On top of that, they were in a dispute with Nurmi over the network’s proposal to buy the rights to Vampira and enter syndication. One week after the Gobel Show appearance — and just a year after Nurmi’s breakout Channel 7 debut — KABC pulled the plug. Contractually, Nurmi was prohibited from appearing as Vampira for six months. But she did own the character, after all. In 1956, at the conclusion of Nurmi’s non-compete, Vampira got a second wind when the program was picked up by KHJ Channel 9. Alas, the revival proved fleeting, and The Vampira Show was canceled a second time. That same year, Nurmi was cast as Vampira in Ed Wood’s low-budget sci-fi horror flick, Plan 9 From Outer Space. The film, about a group of extraterrestrials raising Earth’s dead to stop the living from creating a doomsday weapon, was an utter embarrassment. “The dialogue was so terrible I played the part mute,” Nurmi later recalled. “I couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to see it.” (Not yet, anyway.) Nurmi’s job prospects were drying up, and her personal life was unraveling. Aside from the disintegration of her marriage, Nurmi’s friendship with James Dean had faltered amid his meteoric rise. Asked about his association with the woman behind Vampira, Dean reportedly told the gossip doyenne Hedda Hopper that he didn’t date witches. The comment felt to Nurmi like a stake through the heart, but that wasn’t even the worst of it. After Dean’s death, the scandal sheet Whisper all but accused Nurmi of casting a spell that resulted in the star’s fatal car crash. “James Dean’s Black Madonna,” the magazine jeered on its cover in Feb. 1956. Distraught, divorced and faced with ever-dwindling opportunities as she descended into poverty, Nurmi essentially became a recluse. Through it all, though, her wry sense of humor remained intact. “I’m in oblivion, and I’m very happy here,” Nurmi quipped when the syndicated columnist Paul Coates managed to locate her in 1962. “What are you doing?” Coates further inquired. “I’m a lady linoleum-layer. And if things are slow in linoleum, I can also do carpentry, make drapes or refinish furniture.” “If you had an opportunity to be Vampira again, would you?” “No. I just attracted a bunch of psychos. And besides, that waist-cincher I wore played hell with my breathing.” Nurmi couldn’t have guessed it at the time, but almost two decades later, opportunity would come knocking once again. 'Go Fuck Yourself'In 1980, the film critic Michael Medved and his younger brother, Harry, published a book called The Golden Turkey Awards. Two years earlier, their previous book had solicited votes for a “reader’s choice” award christening the Worst Film of All Time. They received more than 3,000 ballots, from which an overwhelming victor emerged: Plan 9 From Outer Space. This was a welcome development not just for its auteur Ed Wood (now dead several years) whose name was plucked from obscurity, but also for Nurmi. The publicity around The Golden Turkey Awards and an accompanying film festival breathed new life into a movie so bad that it was, in fact, good. With the fresh interest in Plan 9 came renewed curiosity in Vampira, who soon landed on the radar of Walt Baker, the program director at Nurmi’s former employer, KHJ Channel 9. In the 1970s, KHJ had cycled through three hosts for its late-night horror programming. There was Seymour (Larry Vincent), Moona Lisa (Lisa Clark) and Grimsley (Robert Foster). Now the channel was in the market for a new personality to helm the show. Baker sensed an opportunity. He got a hold of Nurmi through an intermediary and invited her to meet with him at the same station from which she had been canned nearly 25 years earlier. Nurmi was now 60, and not in great shape. An autoimmune disease had robbed her of her health. She required the use of a cane. Her mouth revealed missing teeth. She would always be Vampira, but she had aged out of playing Vampira, which meant that if the legendary character was to rise from the dead, KHJ would have to get creative. Accounts of the 1981 Vampira revival diverge, but the gist of it goes something like this: Nurmi and KHJ initially struck a deal in which Nurmi would receive a producer credit and a weekly royalty payment for the use of Vampira’s name and Nurmi’s participation in the show. Vampira would be played by a younger actress yet to be determined, with Nurmi occasionally appearing as Vampira’s mother. Nurmi had her own ideas about who should embody her cherished creation, but KHJ settled on Peterson, a minor actor who’d recently lost out on the role of Ginger Grant for the third Gilligan’s Island TV movie. Peterson wasn’t familiar with the original Vampira Show. But she shared with Nurmi an affinity for Morticia Addams (and both had the distinction of having memorable encounters with Elvis). “Maila and I had a lot in common,” Peterson recalls in her memoir. “She had previously worked as a showgirl and modeled for men’s magazines before turning to horror hosting. She’d even worked as a hatcheck girl like me. And according to Hollywood legend, she was a bit of a star-fucker as well.” In the summer of 1981, Nurmi, Peterson, Baker and other KHJ executives sat down for a meeting. It didn’t go well. “She rambled on incoherently about subjects that didn’t relate at all to what we were there to discuss,” Peterson wrote. “She talked a lot about her relationship with James Dean, but in the present tense, as if it was ongoing. I wasn’t all that familiar with James Dean, but I knew enough about him to know he was dead. It was sad to see an older lady like her alone and down on her luck. I was happy the show would be an opportunity for her to make some money for the use of the Vampira name.” Plans for the reboot proceeded, but the relationship between Nurmi and KHJ turned increasingly sour. Ultimately, Nurmi felt she was being iced out of the creative process. “Go fuck yourself,” she claimed to have snarled at KHJ’s Baker. Vampira would not be back on television after all. In Peterson’s recollection, she was all dolled up in costume on the first day of filming when Baker came bounding onto the set. “STOP THE SHOW!” he barked. “Maila Nurmi’s attorney just called. We can’t use the name Vampira!” The show’s director, Larry Thomas, had an idea. Everyone on set at that moment — himself, Baker, Peterson, cameramen, sound guys, etc. — would think of a spooky character name, jot it down on a scrap of paper, and drop their entry into an empty Folgers coffee can. Then, Peterson would pull out one of the scraps at random. “El-vi-ra?” she grimaced, reading the winning entry aloud. The rest was history. Finding Her Punk 'Fellow Soldiers'At the end of October 1981, just a month after the premiere of Elvira’s Movie Macabre, a profile of Nurmi appeared in L.A. Weekly, an alternative publication that had emerged three years earlier as the city’s subcultural paper of record. The author of the piece was Pleasant Gehman, who’d inaugurated the Weekly’s popular gossip and nightlife column, “L.A. Dee Da.” “Hollywood legends are made, not born, as the old saying goes,” Gehman wrote. “And most of the legends are made, at least in part, by untimely deaths . . . Vampira is not dead. (Well, she always was, anyway.) . . . Today, Vampira leads a quiet life in East Hollywood, working as a waitress and selling various items at swap meets and flea markets. She shares her small apartment with three dogs and tries to keep a low profile . . . This is the perfect time to remember Vampira — her otherworldly beauty, her image as the girl from Screamland, her mysterious personal life. Think of her at the witching hour.” Before plying her trade in journalism, Gehman had burst out of the L.A. punk scene that came roaring to life in Hollywood in 1977. Like many O.G. punks, she had a thing for Gothy motifs, Old Hollywood and mid-century kitsch. Vampira personified all three. “We became friends,” Gehman texted as I was writing this story. “She was so cool!” Gehman wasn’t Nurmi’s first brush with the burgeoning punk world. In fact, one of the young women Nurmi had scouted as a potential Vampira successor was none other than Gehman’s pal Patricia Morrison, who played bass in the Gun Club and, before that, the Bags. “I was interested in the idea, or at least open to it,” Morrison later recalled. “She was the prototype of that gothic look that we now know all so well and is easily recognized worldwide. She was the original, and to me, no one [else] has come close.” Morrison, as it happens, would go on to marry Dave Vanian, singer of British punk pioneers the Damned, whose 1979 classic “Plan 9, Channel 7” (and the accompanying promotional video) paid tribute to Vampira and her relationship with James Dean: “Two hearts that beat as one / And eyes that hardly ever saw the sun / Hollywood babbles on.”  That was just the first punk tribute to Nurmi. The Misfits, a New Jersey group heavily influenced by B horror and Hollywood lore, recorded their song “Vampira,” also in 1979. Three years later, the band invited Nurmi to join them for a promotional signing at Hollywood’s Vinyl Fetish Records. According to the biography by Nurmi’s niece, they “lifted Maila from the doldrums of despair. In them, she recognized fellow soldiers.” In the punk community, Nurmi found a new tribe that carried her, emotionally at least, through the 1980s. She popped out of a coffin to kick off a Cramps show on Halloween night 1984. She befriended Tomata du Plenty, former frontman of the seminal L.A. synth-punk quartet the Screamers, who helped her land a monthly gig at the Anti-Club performing monologues under the pseudonym Honey Gulper. She appeared in Rene Daalder’s experimental 1986 “punk rock musical,” Population 1, the IMDB page for which page is a who’s who of L.A. punk luminaries, including du Plenty, Tommy Gear, K.K. Barrett, Penelope Houston, Gorilla Rose and Tequila Mockingbird; not to mention Al Hansen and his grandson, a future rock star named Beck. (Nurmi is credited under her preferred moniker of the era, Helen Heaven.) In 1987, Vampira rose from the grave yet again when Nurmi linked up with the lo-fi garage rock band Satan’s Cheerleaders, recording two singles as a guest vocalist. But despite these various creative outlets, and the adulation of underground tastemakers, Nurmi was still broke. Cassandra Peterson, on the other hand, was rolling in it, which only deepened Nurmi’s grudge. The headline of the October 1987 L.A. Times article in which Nurmi lambasted Peterson and KHJ took the conflict public: “ELVIRA VS. VAMPIRA.” Baker defended the station. “We didn’t rip this lady off, I guarantee it,” he insisted. Peterson, for her part, claimed she was mystified by Nurmi’s enmity, saying, “I’d like her to be friendly with me.” The Times, as it turned out, had buried the lead, which revealed itself in the very last line of the piece: “Nurmi’s co-writing her bio — ‘Glamour Ghoul’ — and if she can sell it, she may use the money for a lawsuit.” 'There Is No Elvira'Nurmi’s pursuit of justice was encouraged by the aforementioned co-writer, a journalist and gay rights activist named Stuart Timmons. In 1988, Timmons helped Nurmi find an attorney willing to work on her case, Jan Goodman, who believed she had a shot at demonstrating unfair competition. On Sept. 8, they filed their complaint in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, alleging that Peterson and KHJ-TV had copied the character made famous by Nurmi in the 1950s. The lawsuit cited Elvira’s use of velvet Victorian sofas, tattered black dresses, candelabras, cobwebs, skulls and “other macabre items” to create a “combination of sex appeal, humor and death.” The damages sought? $10 million (about $28 million today). “There is no Elvira, there is only a pirated Elvira,” said Goodman (presumably willing to take on an indigent client for the publicity and potential remuneration her case could bring). He argued that the wealthy Elvira should compensate the aging and ailing Vampira, reduced to surviving on Social Security. “She is very mad. She spent a good portion of her life coming up with a character and a show and used that for many years, and the character was ripped off.” Peterson’s attorneys filed the requisite motions seeking delays and dismissals, and the case wended its way through the U.S. district court. At the end of Feb. 1989, the Honorable Matthew Byrne ruled that Nurmi could seek damages for unfair competition, but not for a violation of her right to publicity. In order to justify the latter claim, he said, an actor’s actual voice, face or name had to have been pilfered. A month later, Byrne finally rendered his verdict on Peterson’s motion to dismiss, ruling that Elvira was more a resemblance to Vampira than an exact copy and therefore giving Peterson the victory. (For what it’s worth, Elvira did come across as something of a gothic Valley girl, in contrast with Nurmi’s spooky film-noir diva.) Nurmi, lacking any means to continue the fight, waived her right to an appeal. “I, Maila Nurmi, aka Vampira,” she told the court in a handwritten document on Nov. 18, 1989, “do regretfully declare that, in view of lack of counsel and further in lack of funds, I have no alternative but to discontinue this action.” The battle of the horror hostesses was over, and Vampira, to her eternal dismay, had been vanquished. 'When the Time Comes to Say Goodbye'The original run of Elvira’s Movie Macabre drew to a close two years before Nurmi even filed suit. The final episode aired on Nov. 2, 1986, by which point Elvira had become much bigger than the show itself. There would be several revivals over the years, the latest of which aired in 2021 on the horror streaming service Shudder: “The one and only Mistress of the Dark celebrates her 40th anniversary with a four-movie special, especially for you!” In addition to TV, Elvira’s career output includes movies, albums and books, most recently Peterson’s 2021 memoir, Yours Cruelly, Elvira, published by Hachette. Now 73, Peterson was in the news just this past week, over a viral video in which she recalled being snubbed by Ariana Grande. As for Nurmi, you could argue that her biggest Hollywood moment came in 1994, with the release of Ed Wood, Tim Burton’s critically acclaimed biopic starring Johnny Depp as the late Plan 9 director. The role of Vampira went to Lisa Marie, lauded in Newsday as “a perfect fit, in all respects.”  In the twilight of life, Nurmi remained proud and protective of her signature character. She participated in fan conventions and adapted to the internet age as best she could, selling autographed memorabilia and Vampira drawings online. “I don’t have any babies or any social history that’s remarkable,” she told KABC’s Eyewitness News, “so I’m leaving something behind, you know, when the time comes to say goodbye.” The time finally came on Jan. 10, 2008, when Nurmi’s 85-year-old body was found in her garage apartment on Serrano Avenue in East Hollywood. Vampira had apparently taken her final breath while watching TV on the sofa, her feet propped up on a plastic white patio chair. The obituary in the L.A. Times ran at half a page, above the fold. “The character Vampira,” a photo caption noted, “won Maila Nurmi . . . short-lived fame and a dedicated cult following. Nurmi claimed that Vampira also was the uncredited inspiration for fright film hostess Elvira.” In 1997, the author and documentarian Ray Greene filmed an interview with Nurmi for a project he was working on about exploitation cinema. Greene, who’d befriended Nurmi three years earlier, included just a snippet of that footage in his 2001 documentary Schlock! The Secret History of American Movies. But he and Nurmi had agreed “that someday, I’d use the 70 or so minutes of video we’d collaborated on to find a way to let her speak.” Their interview formed the basis of Vampira and Me, which Greene released in 2012. (It’s streaming on Tubi, fyi, along with Plan 9 From Outer Space.) A thorough and sympathetic portrait of Nurmi’s life, legend and legacy, Vampira and Me only briefly touches on the infamous Elvira saga, and Nurmi only addresses it in philosophical terms. But her remarks, delivered with a sardonic laugh, are sharp as fangs. “The inventor is rarely honored,” she says. “It’s usually the first person with plenty of money who comes along and grabs it who goes to the bank. I’m the inventor, and I watch the other people go to the bank with my money.” Image creditsLead: Cassandra Peterson at The 26th Annual Grammy Awards (Ron Galella, Ltd. via Getty Images); Maila Nurmi as Vampira, 1954 (Bettmann via Getty Images); Chaise lounge (bluefern); Skull (Siri Stafford); Plan 9 From Outer Space (LMPC via Getty Images); Candelabra (Liubov Kaplitskaya); Stage spotlight (Nastco)Nurmi in and out of costume: Vampira (Archive Photos via Getty Images); Maila Nurmi at the 1955 Emmy Awards (Michael Ochs Archives via Getty Images); Moonlit night (Milamai); Spiderwebs (smiltena)Peterson in and out of costume: Peterson (MediaPunch via Getty Images); candelabra with wallpaper (quavondo); Gothic crypt (denisik11)Books: Vampira (Soft Skull); Yours, Cruelly (Hachette); Victorian fireplace (IanGoodPhotography); Spiderwebs (smiltena)Follow us: X | Facebook | Instagram | Threads ICYMI

The Optionist, a newsletter about IP |