Crisps de MadridThe unique Madrileño history of everyone’s favourite food. Words and photographs by Abbas Asaria.

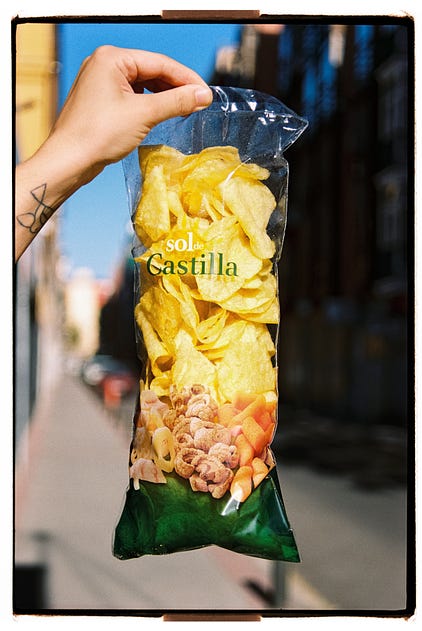

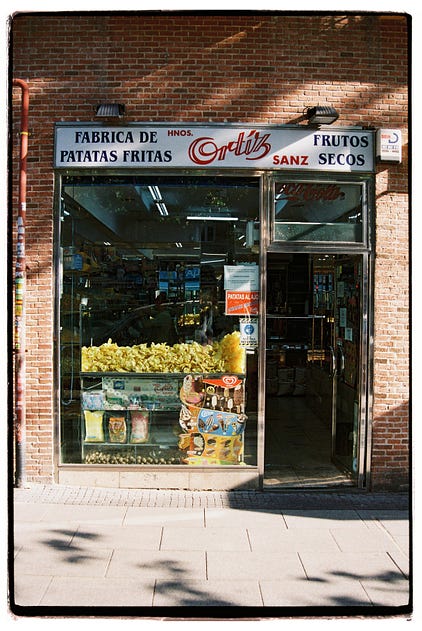

Crisps de MadridThe unique Madrileño history of everyone’s favourite food. Words and photographs by Abbas Asaria. Madrid’s love of crisps is inescapable. The first time I went to a bar by myself to watch a game of football, the beer I ordered came with a small bowl of plain, salted crisps. When I tried to say that I hadn’t ordered any food, the waiter laughed and explained that in Madrid you are often given a free aperitivo with your drinks – occasionally olives, cheese, or cured meat, but very often fresh crisps. If you’re lucky, the crisps will come topped with conservas (tinned seafood): think anchoas (salt-cured anchovies), boquerones (the same, cured in vinegar), or my favourite, mejillones en escabeche (mussels preserved in a curing liquid made from vinegar and wine and spiced with pimentón, which will paint the crisps a lovely burnt orange colour). This combination of crisps and conservas, in which the crisps soak up the fish's brine, quickly became my bar snack of choice. Spain, like the UK, has a big crisp culture, with fun regional differences in how they’re consumed. In Catalunya for example, you’ll often see crisps and berberechos (tinned cockles) topped with Salsa Espinaler during ‘L’hora del vermut’ (‘vermouth hour’) on a Sunday. Spanish crisps even made it into Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite: Galicia’s iconic Bonilla a la Vista salt and olive oil crisps form a part of the dinner the Kim family enjoy at their employers’ expense. (The scene caused a boom in sales of the brand in Korea, where a 500g tin already cost €20.) Spanish crisps have also started to make inroads into the UK. You can’t step foot in a fancy deli without coming across the Barcelona-based Torres, or more recently Superbon’s colourfully packaged offerings, each flavour with a differently designed cartoon bull and the text ‘CHIPS DE MADRID’ stamped on the packet (I’ve never even spotted these in Madrid.) However, Madrid’s fun culture of crisps is different from how Spanish crisps are marketed in the UK, where they’re often found in shops, cafes, and bars aimed at a higher economic bracket and based primarily around flavours such as jamón ibérico, black truffle, fried egg, and caviar (for me, this last one goes too far). Here, while crisps do exist in that luxury bracket, there is also an appreciation of high-quality artisanal crisps in casual settings, as a regular feature of life. Not only are they to be found in bars across the city, but they also light up the streets of Madrid through the windows of glorious little shops known as fábricas de patatas fritas — quite literally, ‘crisp factories’. Take a walk around the city and you won’t be able to miss the fábricas. They are instantly recognisable because of their trademark shop windows, which are filled with golden mountains of unpackaged crisps ready to be shovelled into little plastic bags. ‘It’s a uniquely Madrileño sight,’ Gala Muñoz tells me one day at her shop in La Latina, a twenty-minute walk from my house. ‘Near the coast it’s too humid to have crisps out like this, but even in other regions outside Madrid I’ve not seen similar shops.’ Gala runs Patatas Fritas El Cisne’s nine shops with her siblings; the family business was started by her father when she was seven. El Cisne is one of one of six or seven large companies that comprise the majority of Madrid’s eighty or so crisp shops. Their fábricas are among Madrid’s most recognisable; with half their shop windows filled with crisps, and the other half with colourful kids’ figurines. They also produce my favourite crisps in town. Most of the fábricas, including the largest chains in Madrid, are long-running family businesses with lovely histories, where you can often find the founders or their children behind the counter, greeting regular customers by name. There’s a wonderful old-school kitschiness to these places too, with their glass and chrome counters, colourful shop signs with old-school fonts and neon lights. Frutos Secos Las Ventas takes it up a notch with a coin-operated car-shaped Bugs Bunny for kids to ride outside, the same colour as its bright yellow shopfront. Another fábrica, Frutos Secos Pintado, has a bright yellow exterior too, though this contrasts with a shop window filled with large pink flamingos. ‘It’s one of my favourite things about not being part of a chain,’ Luz Garcia from Frutos Secos Pintado, tells me. ‘I change the decorations every three months to my tastes, and it’s really nice to see how my regular customers get excited about what’s coming next when the seasons change.’ Madrid’s fábricas have been around for some fifty-to-sixty years. Most have their origins in Madrid’s churro culture. Back in the 1960s, Madrid’s crisps were typically fried in churrerías (churros shops) in the city, before the two professions diverged. Enrique Ortiz and Julián Garrido, the respective founders of Hermanos Ortiz Sanz and Sol de Castilla, Madrid’s largest fábrica chains, both moved to Madrid as teenagers in the 1960s to work in churro shops, came back from military service and tried to make a living as taxi drivers, then returned to what they loved: frying churros and crisps. Now this type of hybrid fryer has been lost to time. ‘As time went on, people ended up focusing on either one or the other, since it became too much work to do both,’ Alberto Cuenca, one of the owners of family-run Churrería Julian Cuenca de la Fuente says. ‘We still sell crisps because our customers want them, and the older ones are used to purchasing them with churros. But we get them from another fábrica.’ As Alberto notes, while you can still have your churros hot and fresh out of a pan in Madrid, gone are the days you can say the same about crisps. Places that fry crisps have been subject to a number of regulations over the years (for example, the type of ventilation equipment required), which means they need larger spaces that aren’t compatible with a small shop in town. As a result, the businesses that wanted to continue frying crisps ended up moving their production to industrial estates in the suburbs. This wasn’t something all crisp producers (particularly smaller businesses) were able to do, so nowadays you’ll find companies such as Sol de Castilla and El Cisne supplying smaller crisp shops, churrerías, and bars as well as managing their own production and stores. ‘Some churrerías even ask for their crisps in plain packaging without our logo,’ Gala tells me, with a glint in her eye, ‘so they can keep up the appearance of frying the crisps themselves.’ Even though this means that immediate freshness is lost, it also means – thankfully – the practice of reusing the same oil across both churros and crisps is no longer in place. Not all fábricas de patatas fritas started in churro shops; some were mobile operations, selling their goods across the city from their bikes. One of these is Guillén Hermanos, a family business that has three crisp shops in the south of Madrid. ‘I remember when my husband and his brother started this business in 1964, because it’s the same year we started our relationship,’ Nieves, who helped to run the business in the years following, tells me. ‘I’d be frying crisps by hand until 3am at our place, and then he would load them onto his bike and cycle around town selling them: at bars, swimming pools, and outside the cinema at Gran Vía. It was hard work.’ Guillén Hermanos now fry their crisps in a factory on the outskirts of the city, which also supplies a number of other smaller businesses. ‘It’s obviously not the same,’ Nieves adds. ‘But the crisps here in our shop are delivered every day, and freshness is maintained.’ Like Nieves, the other shopkeepers I’ve met across Madrid are very proud of the freshness of their preservative-free crisps, with deliveries arriving every one or two days from the fryers. All of this contributes to a simple, delicious crisp that needs no adornment. The crisps usually arrive at the shop window having been made with just two ingredients – potatoes and sunflower oil – and upon ordering you’ll be asked if you’d like some salt shaken into the bag. Given their simplicity, the differences between different fryers are subtle, but they still exist: Sol de Castilla boast about frying their crisps at a lower temperature that gives a less fatty, crispier texture, while the crisps from El Cisneuse are fried in a blend of sunflower and olive oil that gives a slightly more intense flavour. Very occasionally you’ll see flavoured crisps already bagged up behind the counter – Guillén Hermanos do a wonderful patatas de ajo (garlic-flavoured), for example – but for me, nothing beats them with plain salt. While it’s the piles of crisps in the fábricas’ shop windows that will catch your attention on the street, there are many other things that keep it once you’re inside. They sell a wide variety of nuts and dried fruit, and a number of shops will roast their own almonds and peanuts on site. Many also have pistachios, cashews and other nuts in little clear, plastic drawers, which also house a number of boiled sweets in differently coloured shiny wrappers. I recently bought some huge, juicy dates from one of the Sol de Castilla shops, while my friends who live around Puerta del Ángel rave about the dried figs you can find at La Golondrina when the season arrives in October. In some fábricas, you might come across jars of floral honey and beautifully patterned tins of preserved tuna, and plenty of shops have a refrigerated counter with trays of olives from different parts of the country sitting in flavoured curing liquids, in addition to other pickled delights such as garlic, onions, and sliced aubergines. Some customers even ask for some of the olive liquid to be poured into their crisp packets, though this divides opinion. ‘My crisps are too good for you to do this,’ Gala tells me, refusing my request to try them. As I’ve gotten to know Madrid over the last decade, I’ve come to love these fábricas de patatas fritas as an integral part of the city’s cultural and culinary landscape. It’s also been interesting to reflect on Madrid’s love of crisps as a newer resident – especially in comparison to London, where I’m from. Like Spain, there’s no doubt we’re a crisp-mad nation, consuming the most crisps in Europe. Even if we don’t clearly see it ourselves, we have a distinctive crisp culture: from our lunchtime meal deals and the way they’re torn open and laid flat to share at the pub table, to endless debates about what makes the perfect crisp sandwich and the appearance of Nigella Lawson’s crisp cauldron at major national events. What makes the fábricas interesting from the British perspective is their continuation of a tradition that exists outside major corporations. In British cities, a combination of our consumption habits, monopolisation, and the contraction of the high street have been very successful at decreasing the amount of space for similar specialised food businesses like sweet-shops and confectioners’ stores. In Madrid, the same thing is starting to happen, with a number of beloved local businesses – such as offal fryers and shoe shops – closing due to real-estate speculation and the growing number of AirBnBs (98% of which are thought to operate illegally). That said, given the forty-six municipal markets in operation across Madrid, it’s clear that policies have been implemented at one point to protect small food commerce in a way that I haven’t seen back home. While a couple of markets in ‘hip’ areas host food stalls, primarily these spaces are filled with produce specialists: butchers, fishmongers, greengrocers, poultry and game stands, and charcuterie shops. These businesses exist in number outside the markets, too, alongside a fun variety of other niche shops. For example, in addition to our fábricas de patatas fritas, there’s a shop near my house that’s only open on Fridays and mainly sells eggs. Today, it pains me to see that – partly due to the proliferation of supermarkets and convenience stores – fábricas may have seen their heyday. Several residents and owners of fábricas contemplate that their best times may be in the past. Meanwhile, Luz tells me how most of her customers are older people who’ve been customers for a long time. ‘We do get their children coming as customers as well, but in general younger people buy and eat in a different way now. They’re more health-conscious and buy more natural things from us, like the nuts and dried fruit,’ she says. What started as a family business fifty-two years ago is now just Luz and her independent shop in Madrid’s Quintana neighbourhood. If she decides to close up when retiring, her business will be joining the other shops that have gradually closed down over the years. All this makes the way Madrid’s love of crisps physically manifests itself on the city’s streets even more special to me. These are more than just stores: they’re charming windows into Madrid’s past, yet also part of the city’s contemporary fabric, and I’d say that’s all the more reason to appreciate the fábricas in the present. I like knowing that within the fábricas I might find someone who’s lived and breathed crisps all their life. When I ask Gala about her outlook on the future of businesses like hers, she is optimistic. ‘Sure, there are fewer of us,’ she tells me. ‘But those of us that are still here offer something special that people really love.’ Thinking back to one particular shop visit, when large queues of people waited to buy snacks in bulk before Sol de Castilla closed for their August holidays, I can’t help but agree with her. Considering Madrid’s endless love for crisps, its fábricas de patatas fritas won’t stop lighting up the city any time soon. Credits

You're currently a free subscriber to Vittles . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |