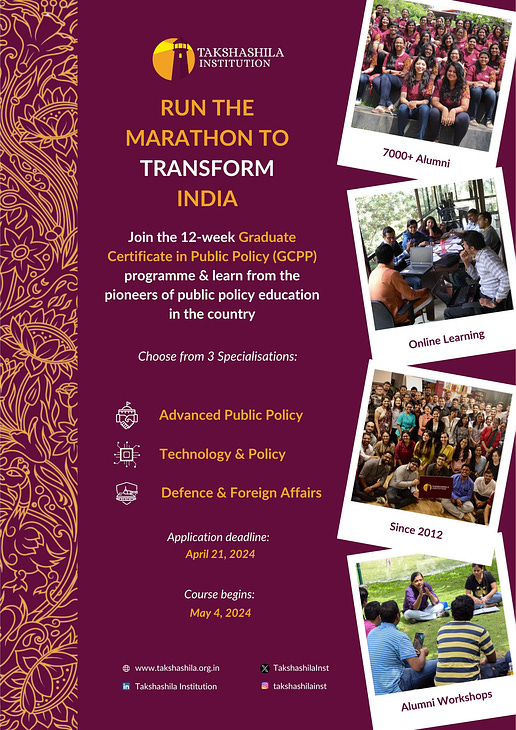

While excellent newsletters on specific themes within public policy already exist, this thought letter is about frameworks, mental models, and key ideas that will hopefully help you think about any public policy problem in imaginative ways. If this post was forwarded to you and you liked it, consider subscribing. It’s free. #250 When You Ignore the Unintended...An Apple A Day For US DoJ, Insoluble Water Problems, Insoluble Alcohol Excise Problems, and a Poor Defence of Wealth TaxCourse Advertisement: Intake for the 38th cohort of the Graduate Certificate in Public Policy Course (GCPP) closes soon. The GCPP will equip you with policy fundamentals and connect you to over five thousand people interested in improving India’s governance. Check all details here.Global Policy Watch: An Apple A Day For US DoJGlobal policy issues relevant to India— RSJOne of the predictions I made at the start of the year was that US antitrust authorities (FTC, DoJ, etc.) were working against the clock to file suits against Big Tech before the end of the current Biden administration. Therefore, I wasn’t surprised to find an eighty-eight-page document from DoJ suing Apple for maintaining an illegal monopoly over its iPhone ecosystem and, in the process, harming the interests of customers and developers. But why they seem to be in such a hurry is beyond me. It is not like if they don’t get voted back to power, the Trump administration will undo everything they have done against Big Tech so far. In fact, suspicion of Big Tech is possibly the only thing that’s common to both the Democratic and the Republican camps. The left-leaning wing within Team Biden, which seems to have taken over this part of the administration, believes Big Tech abuses its monopoly power and harms consumers. In what ways I seem to have difficulty in understanding. For instance, when the FTC sued Amazon last year, the gist of their complaint was Amazon keeps its prices low now to lure customers in. It will surely raise it in future, so we must act now to prevent a future crime. That’s Orwellian enough. Their other grouse was that by keeping its prices low and making losses, it doesn’t allow other small companies from entering into the market who will presumably charge more than Amazon. How that would be good for customers wasn’t clear to me. Anyway, the idea behind that lawsuit was that even if Amazon made losses, it should be controlled so that it wouldn’t make supernormal profits in the future. Going through the Apple suit, the argument is that it has created a closed ‘garden’ for its customers that prevents them from freely interfacing with other competing operating systems or devices. This locks in the customers, and from there, Apple leverages this moat to charge developers and other apps exorbitant sums to access this user base. I have some sympathy for some of this argument. But not much. There’s no monopoly Apple has for any customer to choose an iPhone or iPad to begin with. These products tend to be expensive, and the market is full of smartphones that promise better features at lower prices. The customers choose Apple, often queuing up at storefronts and paying a significant premium because it has some strange alchemy of design chops, innovation and brand image that they feel is worth it. Customers have the choice not to buy it, and in most markets, they have exercised it quite well. Once you’re an Apple customer, you can leave it if you so desire. Apple is possibly a better guardian of customers’ data than most Big Tech companies and it does so by keeping a fairly tight control over who they allow into their ecosystem. If regulators want to level the playing field for the services Apple charges to the app and developer community, there are multiple ways of doing it (as the EU has done just last week) than to go full tilt at breaking it up. It is no wonder Apple has promised to fight it out. And even that is somewhat irrelevant because I suspect a lot of this is merely political posturing at this moment in the election cycle. After all, the antitrust process can take years, with multiple levels of litigation at various courts before a final decision is taken. This is understood by all parties involved. The salvos that will be fired between now and November will be performative to a large extent. Separately, I was quite taken in by this interview with Hina Khan, the chair of FTC, that she gave to Ink, an online publication this week. I have quoted her responses below, which seem to suggest we are in some kind of civilisational conflict with Big Tech. I will leave you to judge for yourself.

In the history of free market capitalism, I struggle to find a single company that has sustained any period of real market dominance that went beyond three decades. But I can quote you many examples of organisations that have sustained monopoly because they were safeguarded by the state with the idea of safeguarding people from market monopolies. This has played out not too far back in time. There's a living memory of this across nations. In response to another question, Hina Khan has this response:

So, the idea is to not just ex-ante take decisions anticipating market gouging pricing like in the case of the suit against Amazon, but also to aim for going back in time and extracting money out of these enterprises for supposedly running a monopoly in the past when there was no case against them. It is a bizarre argument, and worse, it is a dangerous argument from someone who chairs the FTC. It is how you kill enterprise. India Policy Watch #1: Insoluble Water ProblemsPolicy issues relevant to India— RSJThe water crisis in Bangalore and other cities has brought to the fore again the real problem of urban management in India. It is difficult to know where to begin looking for a solution. The classic government response is to blame people who are coming into urban agglomerations like Bangalore. Or asking corporations to set up centres in other cities to decongest metropolises. Unfortunately, it doesn’t work that way. Cities have networks, provide opportunities, and reduce transaction costs. Cities aren’t built by diktats. They grow organically, and bigger cities are the surest way to improve economic and social mobility. We must find ways to govern them better. But how? I think it is one of the most important public policy issues for India in the next decade. Right now it looks almost insoluble. Talking of insoluble, I read this piece of Janan Ganesh in the Financial Times about the blight of insoluble problems facing the world today that made me wonder whether worrying about them is an optimistic or a cynical stance:

Rational despair, indeed. India Policy Watch #2: Insoluble Alcohol Excise ProblemsPolicy issues relevant to India— Pranay KotasthaneWatching the Delhi Excise Policy saga unfold gives me a horrible feeling of déjà vu. It reminds me of the infamous 2G “scam”, in which a presumptive loss of ₹1.76 lakh crores in spectrum allocation was conjured out of thin air. The CBI arrested the then telecom minister on corruption charges. Six years later, in 2017, the court absolved him of the charges. From a policy perspective, this turn of events also resembles the Farm Laws reform saga of circa 2020. In both cases, a progressive policy reform was buried due to poor politics by the governments in charge. I analysed the Excise Policy in edition #182 after it was suspended in August 2022. My assessment was that the government was trying to tap into two revenue sources with that reform. By getting the government out of alcohol retail and distributing those licenses to private players instead, it was trying to mop up revenue from licensing fees. Second, by allowing shops to offer discounts below the Maximum Retail Price (MRP), permitting shops to stay open till 3 am, and authorising bars to serve alcohol in licensed open spaces, it was trying to generate higher excise duty revenue. However, like in the case of the farm laws, it tried to rush this reform without aligning the cognitive maps of powerful rent-seekers. The policy status quo had powerful defenders, many of whom ganged up against the Delhi government. There were also some transient-state shocks which the government failed to anticipate. Some dealers started giving deep discounts to capture the market. That led the government to change the no-MRP policy to a “discount only up to 25% of MRP” policy. After that, retailers started offering “buy one bottle, get another free”. And hence, big dealers could attract more customers, while the smaller ones were finding it difficult to compete. Some licenses didn’t attract any buyers at all. Even though the steady-state promised to be a lot better, the Delhi government made the cardinal mistake of pausing the policy implementation amidst the criticism. Then came the political pushback. Based on the news reports surrounding the case, there seem to be three sets of charges against the policy. The first one concerns notional loss to the exchequer. These charges, as in the 2G case, don’t seem to hold water, especially because the policy was in force only for eight months. At best, they led to a drop in collection during the botched-up transition phase. The second set of charges alleges favouritism in the allocation of licenses. The truth can be uncovered only by the courts. But at this stage, any thinking Indian would not even shrug her shoulders if you were to say that license allocations involve favouritism and clientelism in India. The third set of charges alleges that the money gathered from this policy change was used to influence elections in Punjab and Goa, again a charge that can only be proven by the courts. Whatever the direction this case takes, two policy consequences strike me. First, no state government will touch its alcohol excise policy with a bargepole for years. Second, I wonder if the Delhi government is reaping what it sowed in the name of anti-corruption. P.S.: I’m not equipped to assess the political ramifications of the Delhi CM’s arrests. For that, I point you to two articles. Pratap Bhanu Mehta’s Indian Express article calls the arrest, in no uncertain terms, “a watershed moment in India’s slide towards a full-blown tyranny.” On the other hand, Shekhar Gupta, in his ThePrint.in piece, argues that the targeting of the AAP has reduced India to “a nation of two political forces” until 2029. Also, here’s my interview on the In Focus by The Hindu podcast, explaining the fateful Delhi Excise Policy, in case you are wondering what all this fuss is really about. India Policy Watch #3: Another Year, Another Paper on InequalityPolicy issues relevant to India— Pranay KotasthaneHave you read the new working paper on economic inequality in India? You didn’t miss much if you haven’t. In 2017, we were told that the top 1 per cent of Indians in 2014 cornered 22 per cent of Indian national income, the highest share since 1922 when the income tax was introduced. That paper was titled Indian Income Inequality, 1922-2015: From British Raj to Billionaire Raj? In the latest update to this paper, the question mark has gone away, and the authors confidently tell us that “the ‘Billionaire Raj’ headed by India’s modern bourgeoisie is now more unequal than the British Raj headed by the colonialist forces.” There are four things of note in the latest update. First, the authors claim to have resolved the methodological problems with Indian data this time around. Many public finance experts panned the previous version of the paper for relying on survey data to estimate the incomes of the non-rich but relying on income tax data to estimate the incomes of the rich. Swaminathan Aiyar had written a detailed note on the discrepancies back then, arguing that surveys may underestimate incomes and consumption (try asking a person how much they earn and if they own any wealth). However, the authors insist that “there is no prima facie reason to believe surveys necessarily underestimate a larger fraction of incomes than tax data.” Note that the authors don’t provide any evidence to reject Aiyar’s hypothesis. Leaving the methodological problems aside, it’s not unreasonable to believe that the income share of the top 1 per cent of Indians might have increased in recent years. The K-shaped recovery post-COVID-19 and a spate of pro-business policies—instead of pro-market ones—have increased the market power of a few conglomerates. The reduction in competition should worry us all. On this count, the report does its job. Nevertheless, to argue that today’s India is more unequal than the British Raj is testing the limits of tone deafness. I mean, can someone say with a straight face that the life outcomes of a non-rich Indian relative to a rich Indian today are worse than during colonial rule? I am sure such comparisons are deliberately deployed to ‘shock and awe’ the proletariat out of their collective slumber, but they have the opposite effect of reducing the paper’s credibility. Such comparisons might act as a tool in the hands of those who already believe in the gospel of inequality but do little to convince those who are at the margin. My biggest disappointment is when the authors transform into policy analysts, recommending a two-percent “super tax” on the net wealth of the richest Indian families. Wealth taxes have several problems. India did have a wealth tax that failed miserably. This is a favourite topic of ours, and we have several editions discussing why wealth taxes are inefficient and ineffective. Given that the adverse consequences of wealth taxes are so well-known, I expected that the authors would at least anticipate the unintended consequences and suggest ways to mitigate them. Instead, we get an ideological defence of a predetermined policy idea rather than an empirical one. The solution to income inequality is more competition, not Robin Hood taxes. P.S.: Bertrand Russell’s insight is relevant to this discussion.

HomeWorkReading and listening recommendations on public policy matters

If you liked this post from Anticipating The Unintended, please spread the word. :) Our top 5 editions thus far: |