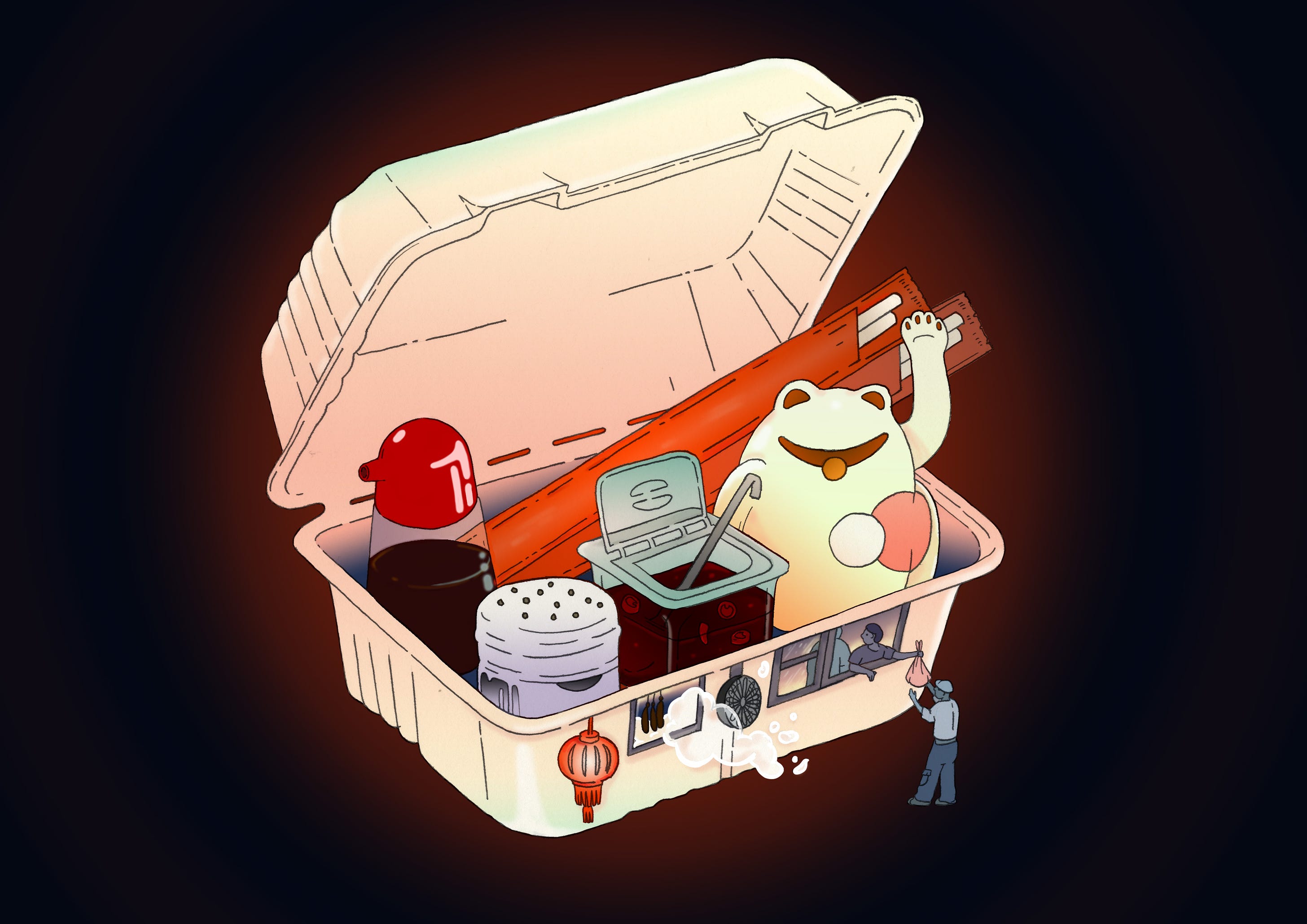

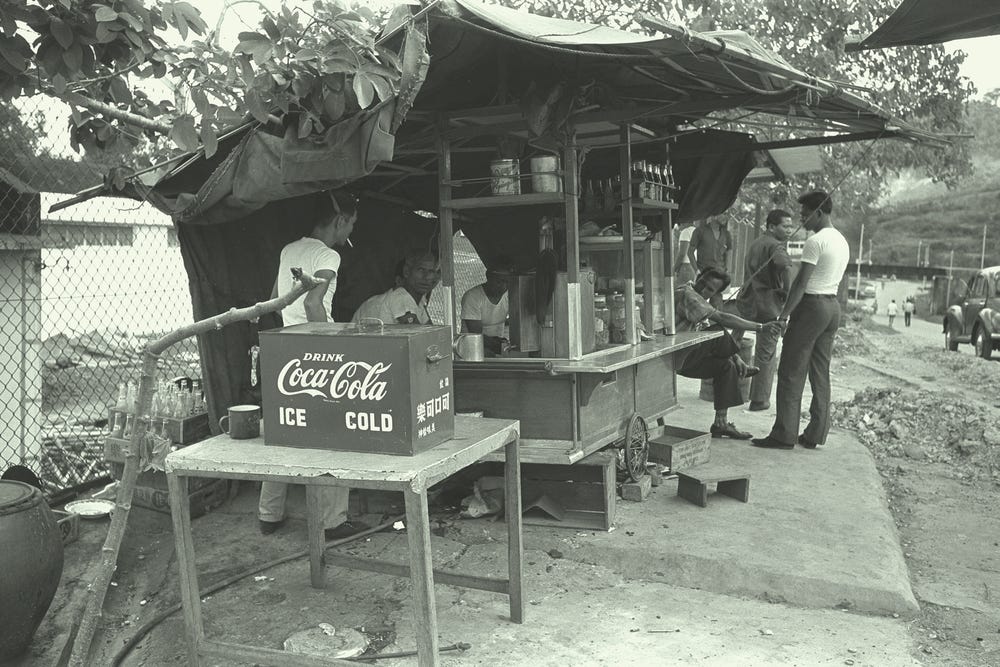

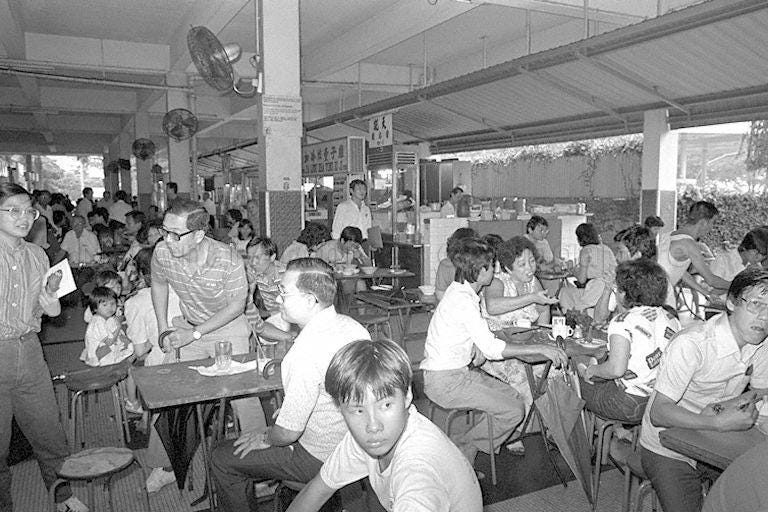

The Life and Death of the Hawker CentreA history of hawker centres, and the evolution of hawker food in Singapore. Text by TW Lim. Illustration by Sinjin Li.Good morning and welcome to Vittles Season 7: Food and Policy. Each essay in this season will investigate how policy intersects with eating, cooking and life. Our thirteenth newsletter for this season is by TW Lim. In his essay, TW writes about how how the food-infrastructure of Singaporean hawker centres has evolved through the decades; and what makes ‘true’ hawker-culture, which may be at the brink of loss today. If you wish to receive the Monday newsletter for free weekly, or to also receive Vittles Recipes on Wednesday and Vittles Restaurants on Friday for £5 a month or £45 a year, then please subscribe below. The Life and Death of the Hawker CentreA history of hawker centres and the evolution of hawker food in Singapore. Text by TW Lim. Illustration by Sinjin Li. In 2022, Urban Hawker – a version of a Singaporean hawker centre – opened right next to Rockefeller Center in Manhattan. Eleven-thousand square feet of some of the world’s most expensive real estate were transformed to house seventeen stalls selling the greatest hawker hits like Hainanese chicken rice, laksa, and Hokkien mee: the food homesick Singaporeans like myself dream of. The place is full of designer furniture, and features a bar that belongs in a swanky hotel’s lobby; there is so much neon plastered around the stalls that the lights overhead are hardly needed. My first stop at Urban Hawker is usually Kopifellas, a stall serving Straits-style kopi (coffee that is dark-roasted, brewed, and poured over sweetened condensed milk, evaporated milk, and sugar) and kaya toast slathered with coconut jam and butter in slowly melting slabs. The first time I visit, I hope that, half a planet away from home, the person taking my order will understand me when I ask for ‘kopi-C, siew dai’. The coffee is fine, aside from being served in a branded paper cup, but what stands out most is that my kopi-C, after tax and tip, comes to US$7 – about ten times what I’d pay in Singapore. My favourite kopi-kia (coffee maker) in Singapore is the guy at the Kim Hwa Coffee Stall in Bedok Block 216, three stops away from Changi Airport on the Metro. Block 216 is a typical hawker centre, slab-faced and unadorned – there’s little more than a roof and a bunch of utilities bundling the stalls together. The cooked-food stalls are wrapped around a wet market, which is filled with vegetable sellers, fish-ball makers and butchers; people do their groceries as others eat. Every surface is hard and washable – tile, plastic, concrete, or stainless steel – and stalls in Block 216 sell braised pork offal, clear fish soups, and crisp-edged batons of radish cake, to be eaten on tables bolted to the floor. There’s an honesty about the utilitarianism of Block 216: the tiny stalls (perhaps a third of the size of Urban Hawkers’), the uncomfortable stools, and the grumpy efficiency of the hawkers. Urban Hawker, on the other hand, feels too nice, too stagey, like an exhibit at a World Fair booth: Hawker Centre of the Future. However, this form, and business model of swisher, reinvented hawker centres is so successful and so replicable that you’ll find food halls like Urban Hawker in most major Western cities – and, increasingly, in Singapore itself. But hawker culture wasn’t built on standardisation and economies of scale. It was built on individual craft and infinite diversity. It was also built on the public-funded capital injection for tens of thousands of micro-businesses owned by working-class families in the two decades after 1965, when Singapore was established as a sovereign city-state. In Singapore, hawker food is utility as well as pleasure, and hawker centres are infrastructure. Contained within this infrastructure is six decades’ worth of changing policies and developments that continue to determine how Singaporeans live and eat. Block 216 was first constructed in the east of Singapore in 1979 and alongside the other 100+ hawker centres which now exist, it feeds millions of Singaporeans every day. Several of its stalls have ‘Chai Chee’ (菜节) in their name – Chai Chee Kway Chap (菜节粿汁), Chai Chee Cai Tao Guo (菜节菜头糕 – radish cake), Chai Chee Minced Meat Noodle (菜市肉脞面) – a reference to the farming village that used to sit less than a kilometre from where Block 216 now stands. When it gained independence from the British in 1963, the island-state of Singapore – a mere 45km wide – was mostly farmland and jungle. Large swathes of the population were farmers who lived in kampungs or villages like Chai Chee, in wooden houses with palm frond roofs. The median monthly wage in 1965 was SG$87 (the equivalent of about £260in 2023), and the unemployment rate was 9%. Hawkers walked through kampungs carrying portable stoves, stopping when someone hailed them. Others set themselves up by the village crossroads, offering an assortment of cooked and raw food. Many of the dishes they sold – like min jiang kueh (yeasted pancakes topped with peanuts and sugar) or ham chim peng (flat fritters with a whisper of salted bean paste swirled through) – are still found in hawker centres today; excellent specimens of both are available in Block 216. After independence, Singapore’s first government, led by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, launched a concerted programme of urbanisation and industrialisation. With no hinterland to speak of and no natural resources to exploit, his government had no choice, as Lee famously said, but ‘to develop Singapore’s only natural resource, its people’. In this period, a governmental body called the Housing & Development Board (HDB) transformed the kampungs of Singapore into public housing estates of high-rise flats with indoor plumbing, gas stoves, and electricity – the kind in which 80% of Singapore’s population now lives. The government built factories nearby, too: Singaporeans, it was thought, would earn more money making Rollei cameras or Varta batteries than they ever had as chicken farmers. Crucially, each housing estate included a wet market and a hawker centre, where hawkers, like those from Chai Chee were resettled. These development policies prioritised citizens’ ability to live well (to keep them happy) and cheaply (to entice multinational corporations to invest in worker-filled Singapore). Ensuring hawker food was still easily available helped achieve these goals, as it meant that more of the population could move to dense urban cores and spend less time cooking, eating, and engaging in domestic labour. However, like the British colonial government before it, the government under Lee considered hawkers a nuisance, incompatible with their visions of the urban, orderly city-state. Hawkers littered and obstructed traffic, and occasionally caused more serious problems, like outbreaks of cholera. But they were also integral to everyday life and could not be discarded altogether. And so, hawker centres were both a solution to “the hawker problem,” and a way of transforming and modernising something indispensable to Singaporean society. When these resettlements were proposed, hawkers were sceptical – not least because they’d have to start paying rent on their stalls. But the government was determined: it subsidised stall rentals and declared that hawkers who didn’t move to a hawker centre had to find other employment (today, it’s hard to say whether the carrot or the stick did most of the work). In those first two decades of independence, the government built some 135 hawker centres, at an initial cost of SG$5 million, with fifty-four centres springing up between 1974 and 1979 alone. In 1985 the last of Singapore’s street hawker was resettled in a brand-new hawker centre, while the building still smelled of concrete dust. While the government’s construction of hawker centres may seem to demonstrate their support, they still considered hawking a backward profession: something people resorted to when they couldn’t find better-paying employment. They had envisioned that the hawker trade would die a natural death when ‘a viable basis for industrial expansion [was] established … and [their] problems of unemployment [became] solvable’, and by the 1990s, unemployment in Singapore hovered around 2%. During this time, the government (still headed by Lee) created policies to discourage Singaporeans from becoming hawkers. Empty hawker stalls were only re-let to Singaporeans who qualified for a ‘hardship case’ scheme – they had to be over forty, with families to support, and no other means of making a living. Because of this, only a handful of new hawker licences were issued between 1973 and 1990. With so many ‘easier’ jobs to choose from, like assembling electronics or clerking in a bank – things with shorter hours and steady salaries – who would need to become a hawker again? The 1980s and 90s also saw the dawn of neoliberalism across the world, including Singapore. The free market didn’t change the way hawkers cooked, but it radically altered their economic prospects. First, the government began to let rental prices in government hawker centres float with the market, rather than setting them as they had done to that point. Secondly, it began to outsource the work of providing hawker stalls to private landlords, to whom hawkers had to pay rent. By the early 1990s, the buildings that had risen from the kampungs twenty years prior were being redeveloped. Hawker centres were among the casualties, and the hawkers they housed were compelled to leave and seek new places of work. These developments created effective diasporas of hawkers and their stalls, such as the one that spiralled out of the Hill Street Food Centre when it was repossessed in 2000. Like the hawkers of Chai Chee village, those of Hill Street are memorialised elsewhere: Hill Street Fried Kway Teow – widely considered to be the best char kway teow stall in Singapore – is miles away in Bedok. Today, my favourite bak chor mee place is in Bukit Batok, the HDB estate in western Singapore where my mother buys her groceries. Here, a heap of noodles is dressed in rendered lard, light soy sauce, and black vinegar; some broth goes in a separate bowl. If you ask for it spicy, as I do, the hawker adds sambal, which turns the sauce rust-red. The canonical toppings include ground pork, slices of pork liver, shiitake mushrooms braised in soy, a few slices of fish cake, sometimes a fish-ball or two, then a scrap of torn lettuce and fragments of ti poh (dried sole) to finish. The whole thing is put together in under three minutes, with a total absence of ceremony: archetypical hawker food. But I don’t eat this dish in a hawker centre; instead, I get it in a kopitiam (Hokkien for ‘coffee shop’) – a collection of cooked food stalls that share bathrooms and a seating area. Kopitiams resemble small hawker centres, but they are privatised spaces, neither built nor run by the government. With Singapore’s exploding population (from 2.4 million in 1980 to 3.5 million in 1995) to accommodate, the HDB built several new towns, Bukit Batok being one of them. Since there were no hawkers to resettle, these new towns didn’t have hawker centres. But hawker food was still in high demand, so, as a compromise, the HDB provided spaces for kopitiams in the new estates.

Although the government was no longer building hawker centres, the number of hawkers and hawker stalls continued to rise throughout the 1980s and 90s; many Singaporeans consider this period a golden age for the trade. There were more and more Singaporeans to feed, and hawkers had become as necessary to the Singaporean diet as rice. Newspapers still write about Tan Kue Kim, who would fry hokkien mee with a gold Rolex on his wrist, wearing a long-sleeved shirt at the wok to remind his white-collar customers that they were his equals. Or consider the Chen Fu Ji sisters, who were a subject of debate in Parliament because they charged SG$25 (around £26 today) for a plate of crab fried rice at a time it was virtually unheard of to charge more than SG$10. Legend has it that they unloaded their supplies from a Mercedes. Despite an increase in the number of hawkers, the new, neoliberal policies set a rent spiral in motion, squeezing hawker incomes even as wages for virtually every other occupation rose. Costs of eating at hawker centres rose, and hawkers were left to deal with rising costs. In 2006, seventy-five-year-old Ho Ng Mui, who ran Yuen Kee Cantonese Braised Duck in the Smith Street Food Centre, said, ‘I leave my house in Kampong Bahru every morning at four o’clock … I’m open for business from 8am to 4pm. I do this every day of the week except Wednesday, when I rest … On average, I earn a net profit of about 1,000 SGD [approximately £590 in 2023] a month.’ (In the same year, the average household income in Singapore was SG$5,730 or £3370.) Yuen Kee, which was started in 1940 by Madam Ho’s father, has since closed down. As the government anticipated all those years ago, Singapore had begun to lose its hawkers – and with them, a taste of its heritage. Affordable, available hawker food has always been seen as part of the social safety net for Singaporean citizens. Today, faced with the prospect of Singapore’s hawkers going extinct, the government has launched a raft of initiatives aimed at preserving the trade. There’s the Incubation Stall Programme, which offers reduced rent on stalls and additional equipment subsidies for first-time hawkers, and the Workgroup on Sustaining the Hawker Trade. Members of parliament occasionally mention the need ‘to ensure... that our hawkers can earn a decent living,’ but when the Workgroup published its report on the hawker trade in 2020, it contained few concrete suggestions on how to increase hawker incomes. It’s as though the goal is to sustain the hawker trade, but without sustaining the hawkers and their lives. Given this, the free market would probably consider Kopifellas a success story. What started out as a food court stall in an industrial area of Singapore in 2017 now operates fourteen stalls in kopitiams across Singapore, in addition to the outlet at Urban Hawker where I’m a regular. Their menu is exactly what you’d expect from the kopi hawker in a kopitiam, and there’s no question that the company has helped fill more hawker stalls. And if a hawker is someone who sells hawker food in something that resembles a hawker stall, there are more hawkers because of Kopifellas too. But while the kopi-kia at Kopifellas (both in Singapore and Manhattan) might be making hawker food, she isn’t a hawker at all – she’s an employee with no meaningful equity in the business, working with standardised ingredients and processes. This is at odds with the hawkers of the first hawker centres, who cooked with some autonomy and worked for themselves. The same is true at dozens of other hawker franchises in Singapore: Selera Rasa Nasi Lemak; the kopi chains Ya Kun and Killiney; Koo Kee Yong Tow Foo; Katong Laksa. While many of these companies did grow out of hawker stalls, today it’s just as easy to buy your ‘hawker food’ from a company that didn’t. Though newer companies capitalise on hawker culture, true hawker centres cannot be replicated and franchised as easily. The culture of eating and cooking that they embody live on in the way you can walk into a hawker centre in Singapore and get three different plates of chicken rice from three different stalls, in the way every plate of char kway teow has a different balance of wok hei, sauce, and texture. This is true of Block 216, but also of the ecosystem of hawker centres, which are not a thing but a system. And their cultures could could not exist without the burst of activity that brought hawker centres into being. Credits

You're currently a free subscriber to Vittles . For the full experience, upgrade your subscription. |