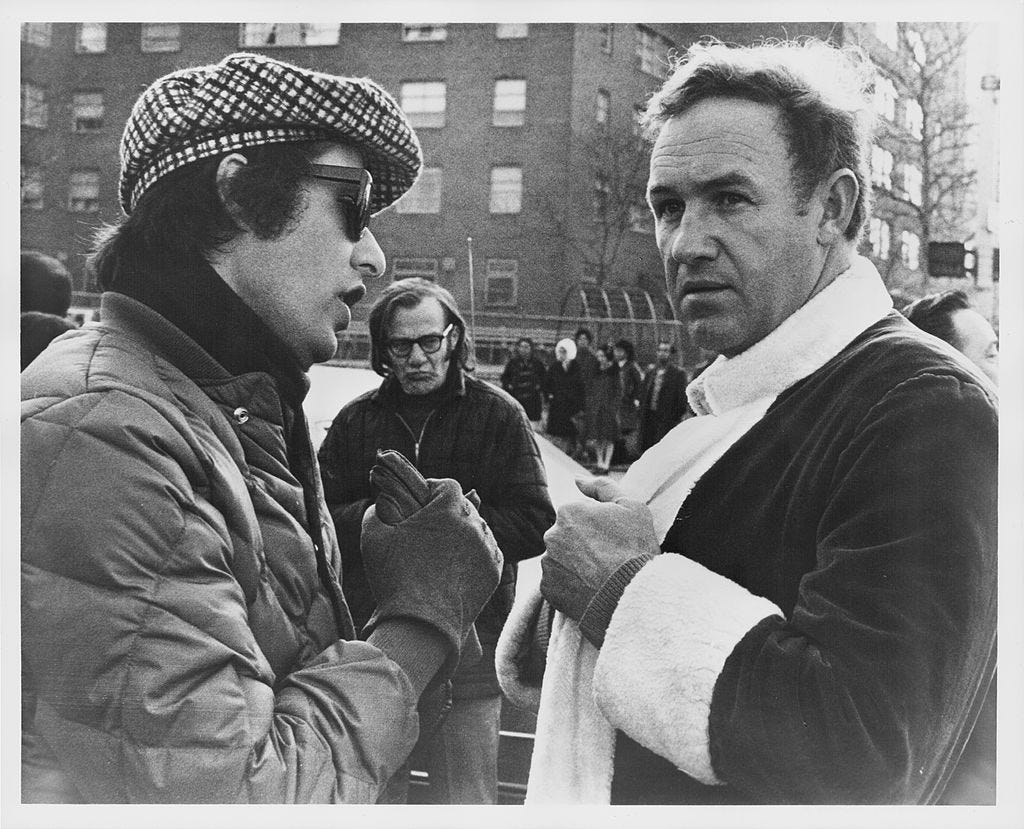

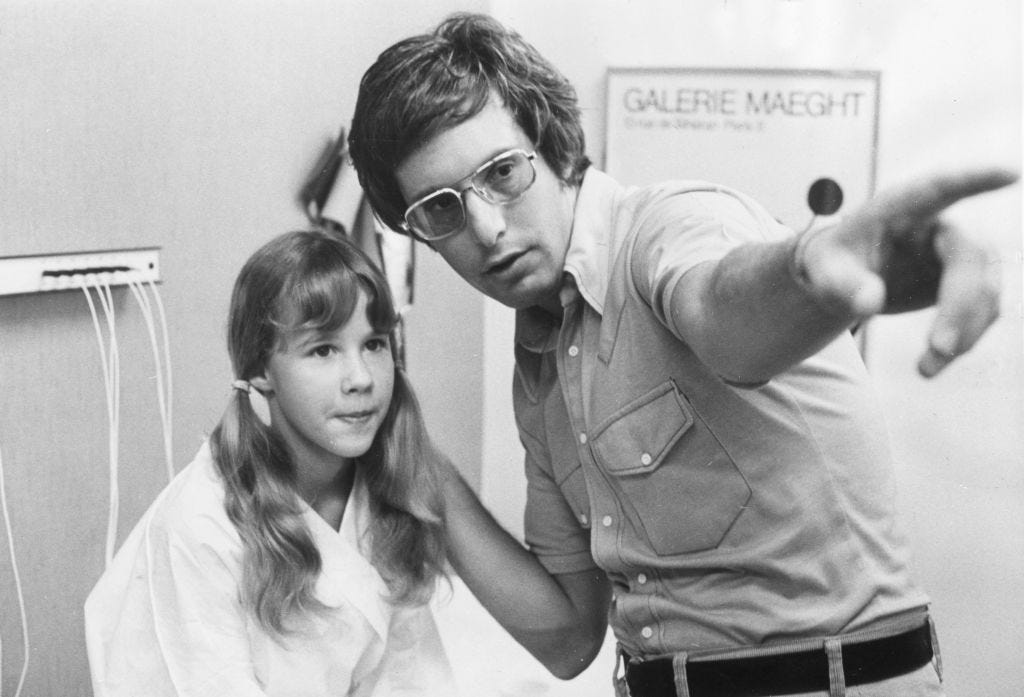

Rushfield: William Friedkin and What Hollywood Has LostThe legendary director would never stand for today's crisis of blandWhat is Hollywood missing right now? Well, where to begin; the list goes on. But "William Friedkin" is as good a place to begin as any. What Hollywood needs, if it's ever going to claw its way back to cultural relevance, I'd say, give us three William Friedkins and we'll rule the world. When you look at Friedkin's world, the breadth of the creative fearlessness, onscreen and off, takes your breath away. As does the notion that not too long ago there was an industry that accommodated that fearlessness. They didn’t make it easy for him — nor he for them — but it’s impossible to picture a spirit like that lasting an hour here in Streaming Wars-era Hollywood. In William Friedkin's world, everything was big and everything was important. There were no small problems, no small questions, and no small films. And in his hands, film was a force to be marveled at and feared, and the people who created it cowered before no one. You can boil down the current state of Hollywood creativity — and its crises — to this: never in history have more artists been more empowered to say more, and never in history have they said less. We have a million voices making films and shows in Hollywood, more than have ever been made before. And it all feels very much… the same. Hollywood is suffering from a crisis of blandness. We speak as a pack, on-screen and off. The films (and the shows, but especially the films) have never played it safer, more predictably. And the personalities who make them have been well trained to behave as dutiful little politicians, offending no one, mildly pleasing all. (Until they get a little toe out of step, and the hammer comes hurtling down on them.) Friedkin did nothing small and nothing safe. Every swing was for the fences because he invested so much thought and passion into every moment. "Operatic" is the too obvious word for the sweeping, grandiosity of his world — not just in the massive productions like French Connection, but in pieces that were technically smaller, like his later productions Bug or Killer Joe that were set mostly in a single room with tiny casts, but contained such sweeping drama and emotion, they felt more grandiose than most modern CGI spectacles. (He went on to actually direct operas for the stage in his later career, which is another thing I would bet not too many of today's directors will find their way to.) A parlor game I have with friends is trying to name the best three-film run by any director; the catch being that almost all who make two home runs back-to-back films miss a step on the third. Spielberg followed up Jaws and Close Encounters with 1941, to give one example. Ridley Scott made Alien and Blade Runner, and then Legend. Runs of three consecutive classics are unicorns in cinema. (This game only works post-1970. Great runs in the studio days happened regularly.) Friedkin's run of Exorcist, French Connection and Sorcerer is generally the final word in the game. (The latter had the misfortune of opening against a little film called Star Wars and was unjustly overlooked but is seen as a classic today.) It’s a breathtaking burst of creative — energy isn’t the right word with Friedkin — intensity. It’s as close to a perfect period as any director gets. But even after that incredible streak, even as his favor in Hollywood waxed and waned and he never again had the same blank check and the same sized budgets, he invested everything he did with so much thought and passion, there wasn't a frame of his career that was ordinary, dull or predictable. And off-screen, whatever the opposite of the politically timid, PowerPoint-driven drones who run Hollywood today are, he was it. The fact that the industry for a time tolerated and nurtured him, give him so much rope… shows what a different place the industry once was. The stories are of course, operatic. Bringing his house painters and a bottle of bourbon to a studio meeting on Sorcerer. A brute, a bully, a profane, totally inappropriate instigator. But he was never small. Think of the typical tentpole director gamely fielding questions at a junket today and compare them to this: Or think of a 2023 director dutifully working their way through the awards circuit, remembering to keep humble, to focus on gratitude and what an honor it is to be amongst such talented people, and compare them with this: My own memory: Sometime in the late '90s I went to a screening of To Live and Die in Lie at UCLA's Melnitz Auditorium. After the film, Friedkin said a few words and took questions. One poor soul, his cinematic erudition fluttering on his sleeve, asked him why he shot the film in some of the more anonymous corners of Los Angeles, why he hadn't used the more classic, iconic locations of the city.

A couple questions later, another audience member got up and asked him about the homophobic subtext in the movie. He stared the questioner down and nodded, "Okay, you got me. I’m a closet queer. You got it out of me. You happy now? So we can talk about the fucking movie?" Not how publicists typically recommend directors handle interactions with the public. I don't think you need to be Caligula to make a good movie. There have certainly been great films (and shows) made by decent, kind and grounded people over the years. (Although curiously, none of them come to mind at the moment.) But neither is it a total coincidence that the period of modern history when Hollywood was at its most vital and relevant, when it set the templates in all sorts of genres that still govern today, it was a time when some very different characters ran amok. And Hollywood, grudgingly made room for people — the eccentrics, the seekers, the people who had visions for things that weren’t anything like what anyone else was making. (Requisite aside: the different characters in those times were of course 100 percent white men, which was not good. Nor were many of the places that white male artistic eccentricities took them. But I still believe that making room for bombastic personalities does not require turning a blind eye to illegal and abusive behavior.) And frankly it wasn't just the directors and the artists who brought these flamboyant personalities to the table — it was a time of colorful and idiosyncratic executives too, who had guts they trusted and made bold and different choices. Right down to Friedkin's wife, the legendary Sherry Lansing, the other half of an impossibly enduring love story and creative mind-meld, and to whom The Ankler's deepest sympathies go today. Artists for a time were not just like us: they were big dreamers and thinkers who did big things and feared for nothing. They made hits, they fought, they loved and often they fantastically flamed out. But they were rarely boring. And no one would have ever suggested you could replace William Friedkin with a computer program. William Friedkin left behind an incredible body of work and an incredible passion for film and for storytelling, and an unmatchable fearlessness — artistically and personally — that Hollywood would do well to get its hands on a few ounces of sometime in the very near future. Can’t afford The Ankler right now? If you’re an assistant, student, or getting your foot in the door, and want help navigating the craziness of this business but don’t have the money to spare, drop me a line at richard@theankler.com and we’ll work it out. No mogul or mogul-to-be left behind here at The Ankler. Follow us: Threads | Twitter | Facebook | Instagram Got a tip or story pitch? Email tips@theankler.com. To advertise to our 55,000 subscribers, email info@theankler.com ICYMI

Strikegeist, a new (free!) strike newsletter

The Optionist, a newsletter about IP |