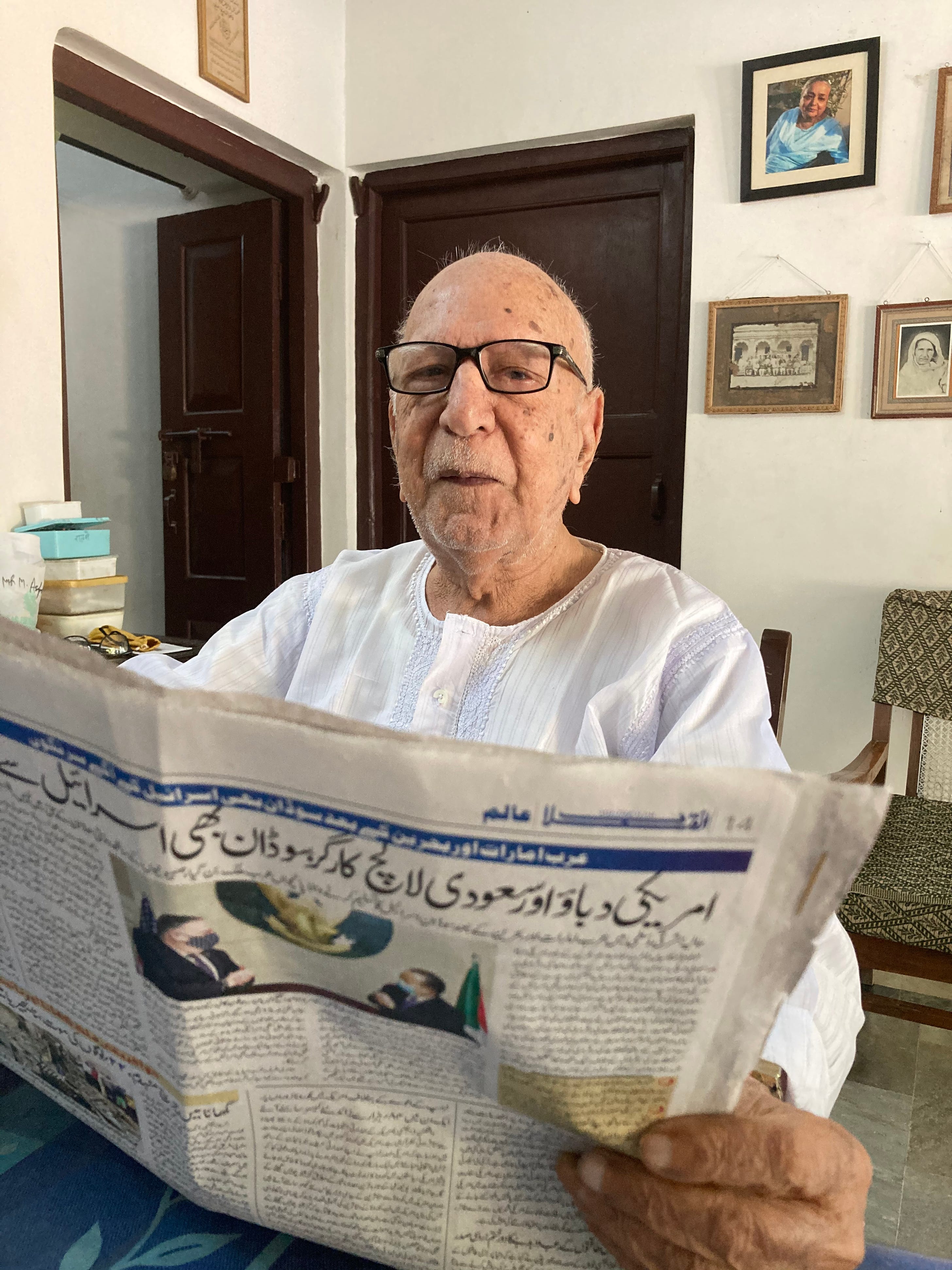

Peace and resistance in times of strifeWelcome to a day in the life of a village in north India aka the badlands of east Uttar PradeshI wake up on the roof, under a pale blue sky. It is ridiculously early. I am on a single bed, with a mosquito net around me, luminous in the light of dawn. The night breeze has been my sanctuary. Another of my daughter sleeping in the adjacent bed. I get out and take another photo of three folding beds in a row, covered by gently swaying mosquito nets in pastel shades, balanced on bamboo sticks propped up on two sides of the beds. When I send these photos to friends and family later in the day, nearly everyone will reply with memories of summer vacations in their childhood when they also slept on the terrace of their homes. Of cooling the floor with water first, then laying the beds. Of gazing at stars and scaring each other with ghost stories. I walk to the parapet wall of the roof and look down at the empty village square in front of our home. Sleeping dogs lie scattered on the brick-layered ground. The village well and mosque on one side. A corner where samosas and tea will be available later in the day. Three rabbits sleep in a cage outside a home. Goats flap their ears to get rid of flies. On the other side, a mud-walled centre is the hub for digital facilities in the village. In the day time, students will gather here for tuitions and to access Wi-Fi. Adults will visit to get their KYC updated in various government welfare schemes and to fill forms online. My daughters and I will go there to access online classes. I will teach and attend meetings on Zoom. We are in Ghazipur district in east Uttar Pradesh. A vast maulshree tree at the centre of the village square is home to the chatter of birds, excited at the prospect of a new morning. In this part of India, the tree is pronounced as mulsari. In the evening, my father-in-law, Mirza Ashfaq Beg, now in his 90s, will sit here on his wheelchair, surrounded by generations of villagers. In another hour, it will be time for school and morning tuitions. Groups of students in uniform, supporting their siblings, chatting with friends will walk past here. Straight-backed girls with hair combed tight will cross on their bicycles, their school bags balanced on their shoulders. This is a new sight here, quickly normalised by the young women themselves. There is an unspoken dread that the tradition of the Muharram procession and the rituals associated with it are under threat. Not all change is progressive. Communities stripped of the permission to express their identity through festivals and rituals in common spaces lose something intangible about their sense of self-worth. Their sense of belonging weakens. On the evening before Holi, the bonfire for Holika dahan is also lit by Papa in this square. Diwali is celebrated here by all communities together. I cannot see the temples of this village from our terrace, but I can hear all of them. They love their loudspeaker technology. Hawkers collect outside the Eidgah with painted mud toys, gas balloons and crunchy snacks for the children who accompany their fathers on the morning of Eid. It has been an annual mela everyone looks forward to. When I stepped out of our home on Eid and saw policemen sitting outside the mosque, on the bench under the mursali tree, I was distressed on behalf of everyone else. I wanted to text a friend. TYPE MY RAGE IN ALL CAPS. Express my incoherent sense of loss. “Empathy deepens us, yet how we unwittingly sabotage our own capacities for it. We care because we are porous. Pain is at once actual and constructed, feelings are made based on how you speak them.” “What is the taaza khabar today, Papa?” I ask him. “Any hot news?” “Nothing in particular,” he says, folding the newspaper. “I heard Mirza Sahab’s bahu is visiting these days. Have the papers reported it?” “I have my sources,” I say, making him laugh. A shorter version of this essay was published here If you feel inspired to support Natasha Badhwar’s writing, do consider become a paying subscriber. |